Abstract: A description is given of the recent meteorite dropping fireball on 2023 February 14, 17h58m UTC and the recovery of the meteorites on 18 February.

Introduction

From the oldest times mankind saw stones falling from the sky but only from the 26 April 1803, when a meteorite fell dropping 3000 fragments in the fields around the village of L’Aigle (France), science accepted the existence of this natural phenomena.

In a few years at the end of 18th century and the beginning of 19th century a certain number of events occurred that brought a revolution in astronomy: the discovery of Uranus the 13th of March 1781 by William Herschel, the discovery of 1 Ceres the 1st of January 1801 by Giuseppe Piazzi and the fall of the meteorites of L’Aigle in France that occurred the 26th of April 1803.

During this thrilling period for astronomy two books were published in the same year, 1794, one by Ernst Chladni: “Über den Ursprung der von Pallas gefundenen und anderer ihr ähnlicher Eisenmassen und über einige damit in Verbindung stehende Naturerscheinungen” (in German) and another one by Soldani: “Sopra una Pioggietta di sassi accaduta nella sera de’ 16 giugno, 1794, in Lucignano d’Asso nel Territorio sanese” (in Italian), both treating the revolutionary topic for that epoch, the fall of stones from the sky.

In fact, it was some decades already that scientists such as the German Ernst Chladni, the Italian Ambrogio Soldani, the French Antoine Lavoisier and some others believed that stones could fall from the sky. Such as was the case with the fall on 26 May 1751 at Hraschina (Croatia), the fall on 13 September 1768 at Lucé (France), the fall on 17 May 1791 at Castel Berardenga (Italy), the fall on 24 July 1790 at Barbotan (France), the fall on 16 June 1794 at Siena (Italy), the fall on 13 December 1795 at Wold Cottage (United Kingdom) and the iron meteorite found near Krasnoyarsk studied in 1772 by the German Peter Simon Pallas.

After the fall of L’Aigle, it took many years before this reality was accepted by all scientists, for example the fall of Weston (Connecticut, USA) on the 14th of December 1807 required a lot of time to be accepted.

In Italy this topic was accepted almost immediately and lists of stones which had fallen from the sky were soon described for events from B.C. The first meteorite fall after 1803 was that of Gerace and Cutro (Reggio Calabria) on the 14th of March 1813, but the first accepted case was that of Renazzo (Ferrara) which fell on the 15th of January 1824. This was a rare carbonaceous chondrite. The list of Italian meteorites from the 19th century corresponds to an average of one meteorite once in each 3 years. Remarkably, in the 20th century the number of cases decreased. Following the theoretical calculations, there should be 3 meteorite falls each year in Italy. We can consider that many of these are missed, but proportional this is one of the best results in the world thanks to the high density of the population and the high percentage of people with good educational qualifications.

Latest meteorites in Italy

In the last years the number of bolides observed has increased since more attention is given to this type of phenomenon. So far, we have now two meteorites in the last three years, the one of the Cavezzo (Modena) fall on the 1st of January 2020 which was found on 4 January (Figure 1) and now we had the fall at Contrada Rondinelle e Contrada Serra Paducci (some km North of city of Matera) which fell on the 14th of February (Saint Valentine) and which was found on the 18th February.

Figure 1 – The two fragments of the fireball that fell on New Year’s Eve and which were found in the Modena area. (Credits: Prisma/Inaf).

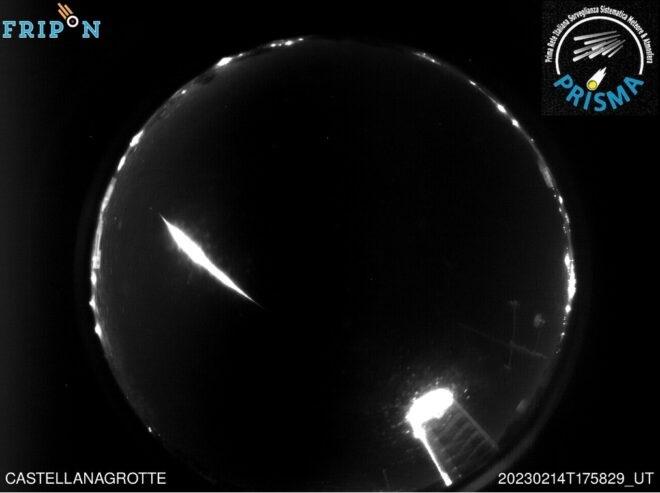

According to the newpapers Corriere della Sera, Il Messaggero and the TV channel RAI, the bolide was accompanied by a roaring sound following immediately after the appearance (Figure 2). A big noise was heard on the house where the meteorite impacted (Figure 3) but only some days later it was noticed that an object had damaged a tile of a terrace (Figure 4) and a solar panel. A meteorite was found, broken in many pieces for a total weight of around 70 gram (Figures 5 and 6). The meteorite is not a solid stone, has a grey color and no chondrules are visible. It is possible that more pieces are somewhere on the ground in the same area.

Figure 2 – The Valentine’s fireball recorded by the Prisma camera of Castellana Grotte. (Credits: Prisma/Inaf).

Figure 3 – The strewn field associated with the Valentine’s fireball determined by the Prisma team. (Credits: Prisma/Inaf).

Figure 4 – The tile of the balcony damaged by the impact of the meteorite. (Credits: Prisma/Inaf).

Figure 5 – The fragments of the meteorite that fell on the evening of Valentine’s Day in the northern area of Matera. (Credits: Prisma/Inaf).

Figure 6 – Collection of fragments found so far. Prisma experts do not rule out that there may also be other pieces in the area. (Credits: Prisma/Inaf).

These two events show that the networks of all-sky cameras may record all, or almost all, meteorites that fall in the future. This should permit to determine the real frequency of the number of meteorites that fall on the Earth.