By Paul Roggemans, Denis Vida, Damir Šegon, James M. Scott, Jeff Wood

Abstract: The Global Meteor Network recorded enhanced activity from the 29-Piscids (PIS#1046) during November 2–9, 2025. In total, 50 meteors belonging to this meteor shower were observed between 218.0° < λʘ < 228.0° from a radiant at R.A. = 7.4° and Decl.= –5.3°, with a geocentric velocity of 11.8 km/s. In 2019 and 2024, the shower also displayed enhanced activity. Mean orbit solutions are presented for these years. This case study confirms the existence of the 29-Piscids and new solutions were added to the IAU-MDC Working List of Meteor Showers.

1 Introduction

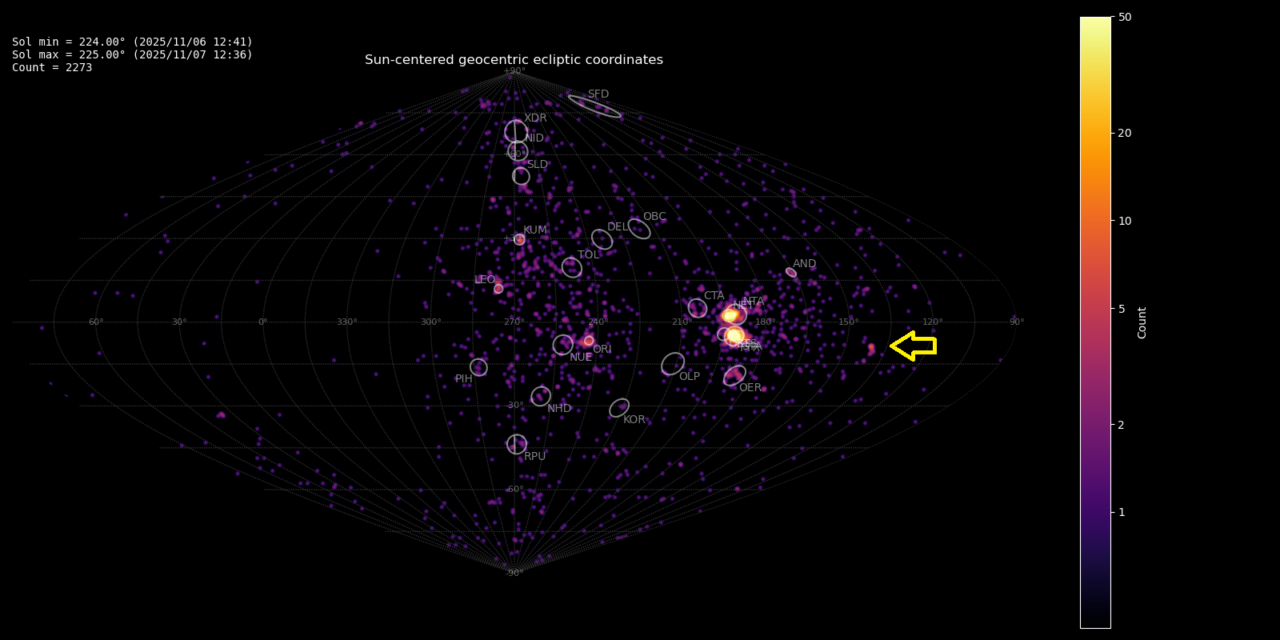

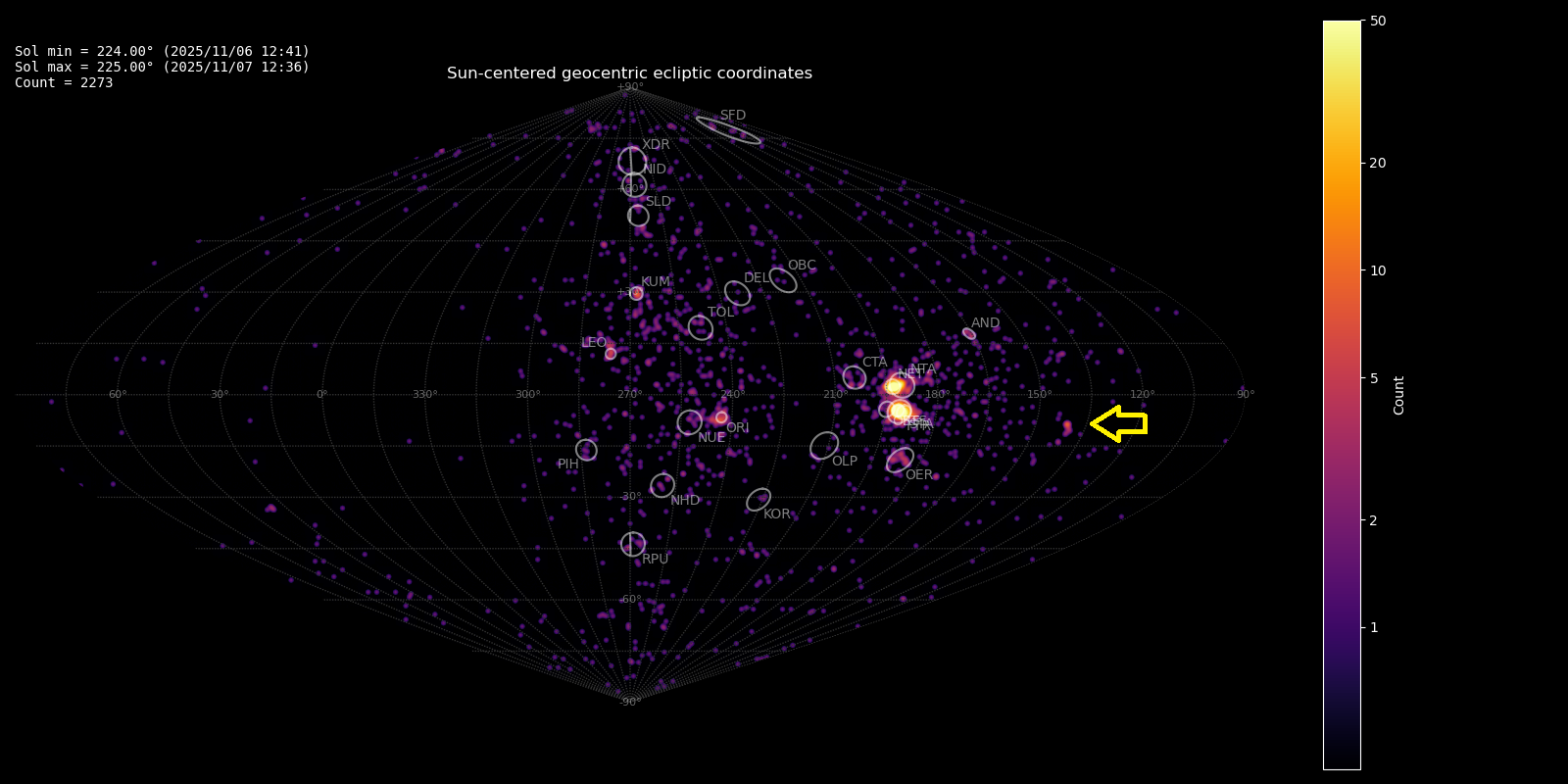

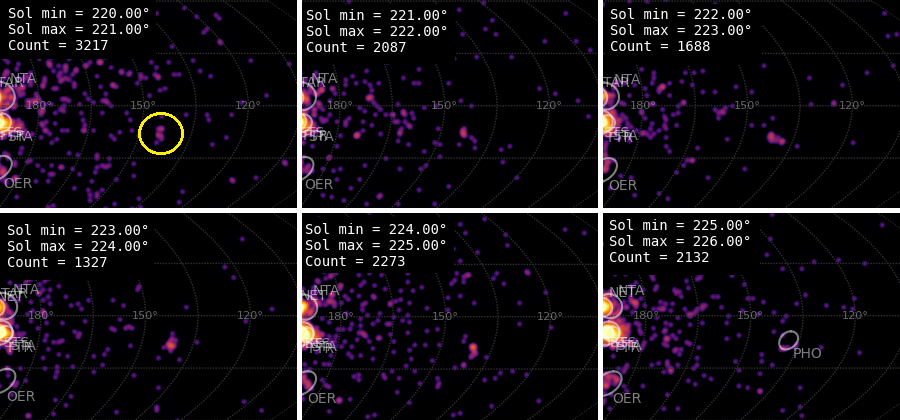

Between the 2nd and 9th of November 2025 an episodic meteor shower known as the 29-Piscids appeared on the radiant density maps of the GMN (Figure 1). This shower was first reported by Jenniskens in 2020. In 2019, a first activity was observed between solar longitude 202.3° to 205.0° with a maximum on λʘ = 204.0° (October 17–18, 2019). One month later, during November 11–18, 2019. Activity stretched between solar longitude 228.3° and 234.9° and peaked at λʘ = 231.4°. Given the similar eccentricity and longitude of perihelion of the orbit both activities were assumed to be related to the same parent body and added to the MDC shower list as one single meteor shower (PIS#1046) (Jenniskens, 2020).

Figure 1 – Radiant density map (sinusoidal projection) with 2273 radiants obtained by the Global Meteor Network during 6–7 November, 2025. The position of the 29-Piscids in Sun-centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates is marked with a yellow arrow.

Figure 2 – The appearance of the 29-Piscids radiant between November 2–8, 2025 (220.0° < λʘ < 226.0°).

2 Shower classification based on radiants

The GMN shower association criteria assume that meteors within 1° in solar longitude, within 1.8° in radiant in this case, and within 10% in geocentric velocity of a shower reference location are members of that shower. Further details about the shower association are explained in Moorhead et al. (2020). Using these meteor shower selection criteria, 50 orbits have been identified as 29-Piscids.

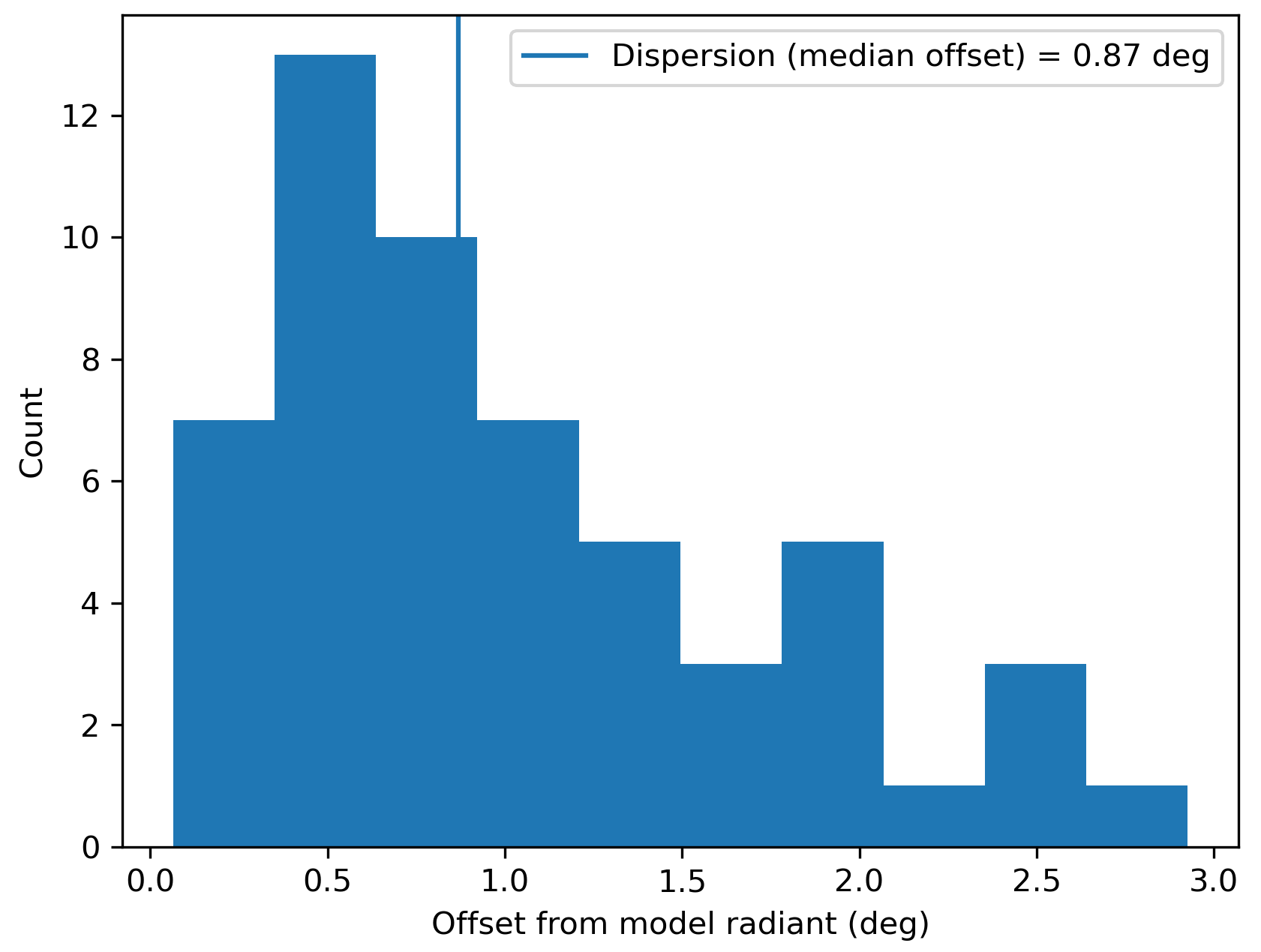

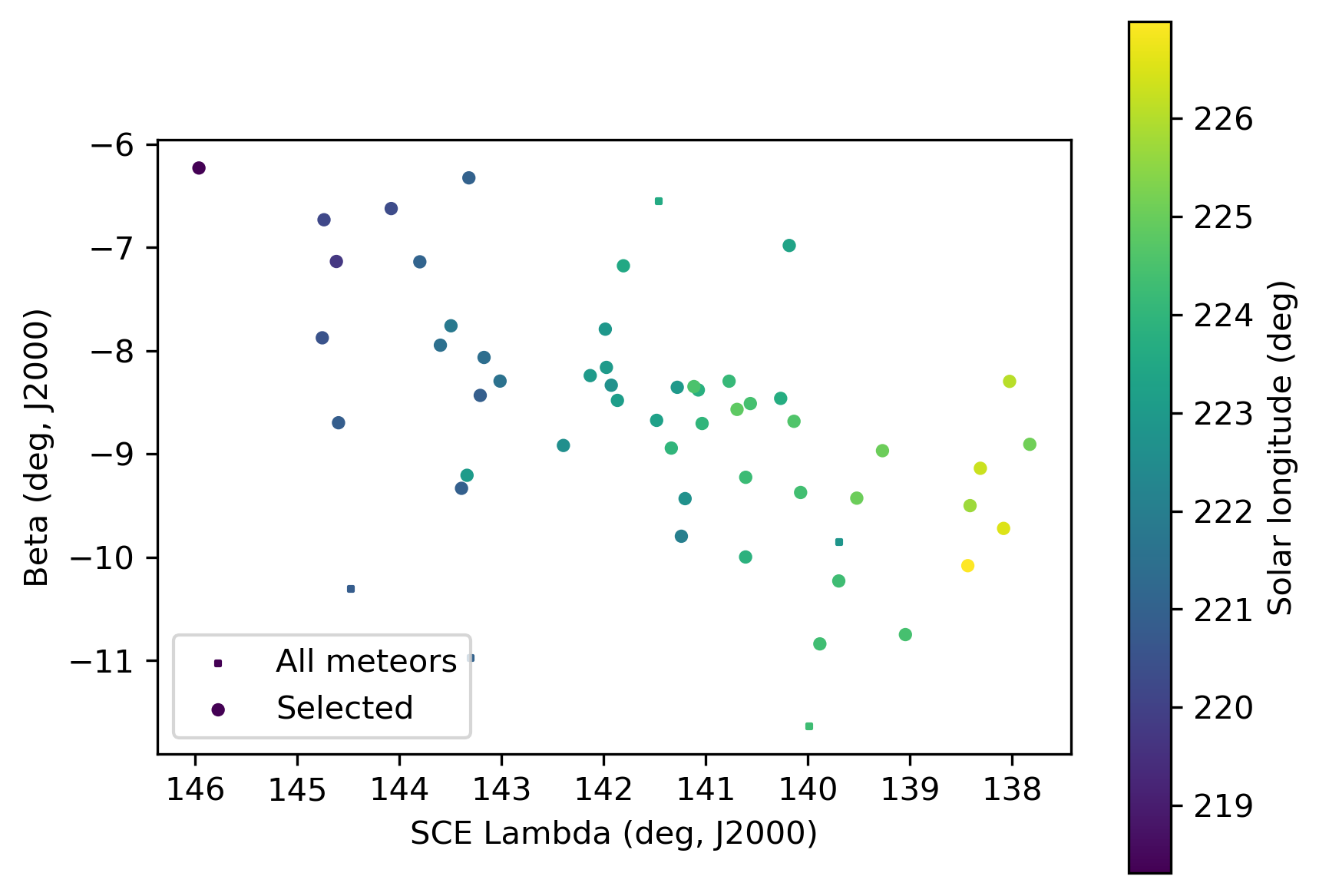

Figure 3 – Dispersion median offset on the radiant position.

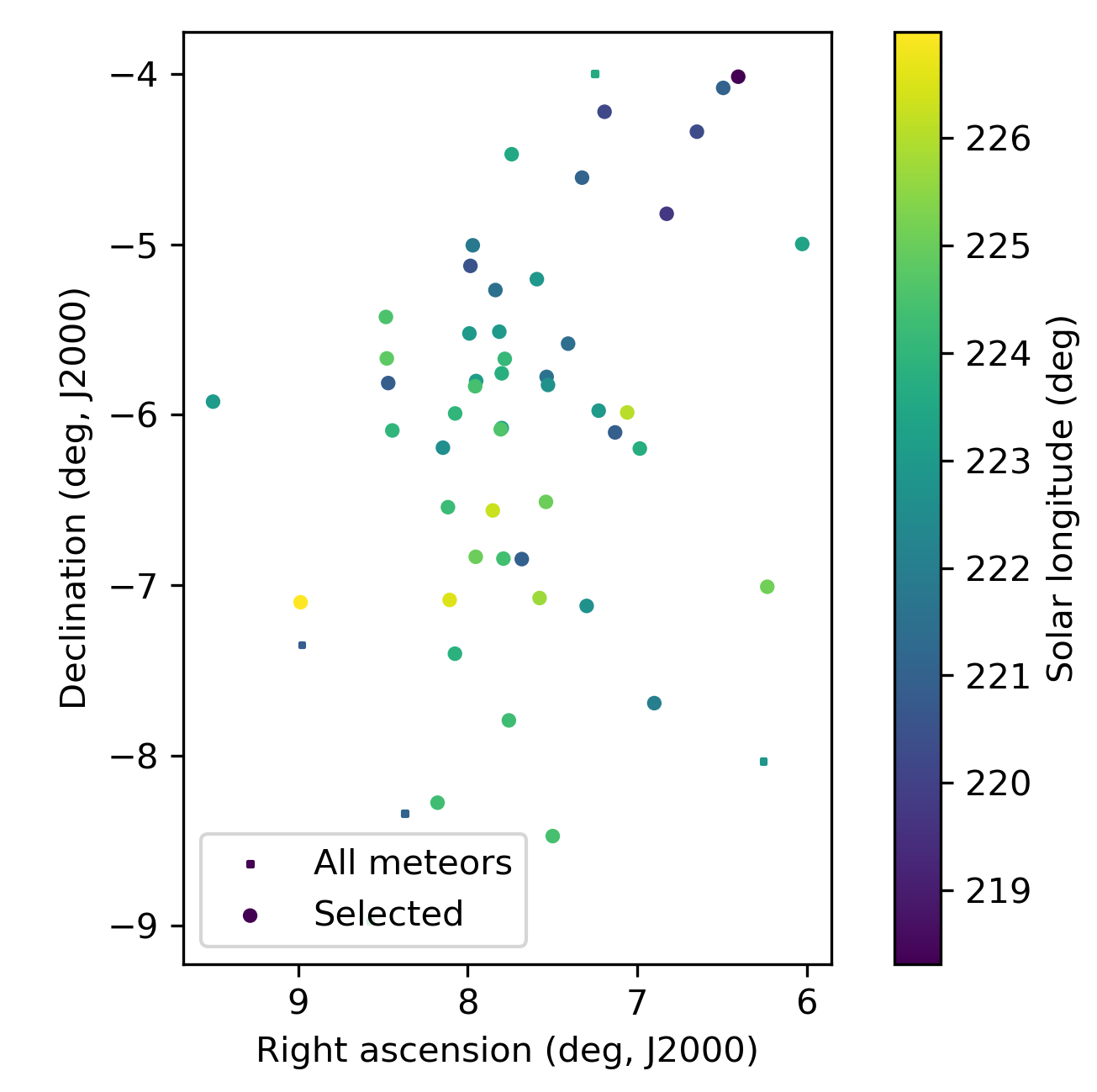

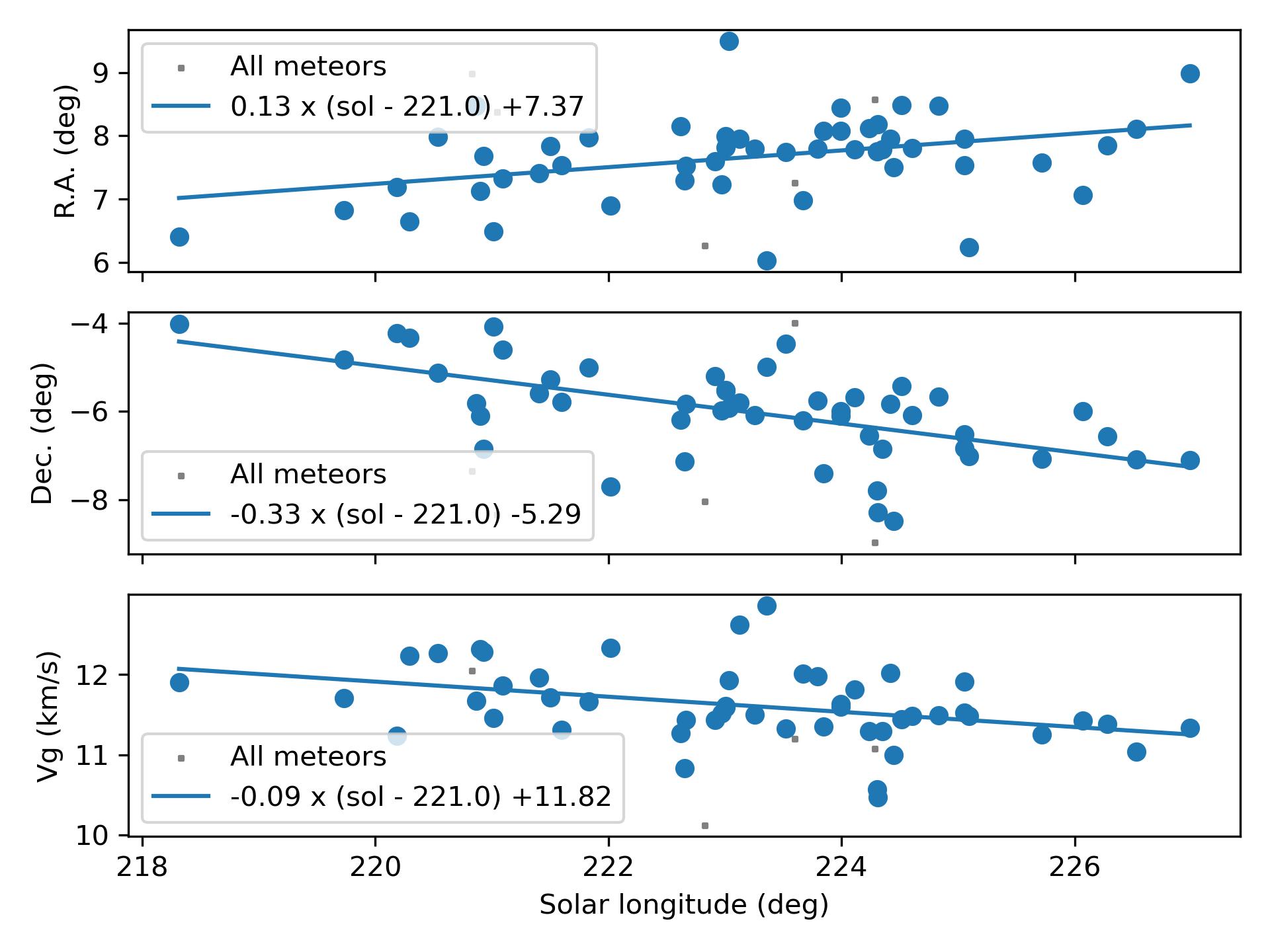

The shower was independently observed in 2025 by 127 cameras in Australia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Belgium, Brazil, Croatia, Czechia, Germany, Netherlands, New Zealand and South Africa, South Korea, Ukraine, United Kingdom and United States. The shower had a median geocentric radiant with coordinates R.A. = 7.37°, Decl. = –5.29°, within a circle with a standard deviation of ±0.9° (equinox J2000.0) (Figure 3). The radiant drift in R.A. is +0.13° on the sky per degree of solar longitude and –0.33° in Dec., both referenced to λʘ = 221.0° (Figures 4 and 5). The median Sun-centered ecliptic coordinates were λ – λʘ = 143.66°, β = –7.79° (Figure 9) with a strong drift in Sun-centered ecliptic coordinates Δ(λ–λʘ)/Δλʘ = –1.01° and Δβ/Δλʘ = –0.35°. This means that one or more orbital elements changed during the transit of the Earth through the meteoroid stream. The geocentric velocity was 11.82 ± 0.09 km/s.

Figure 2 shows how the 29-Piscids radiant changed per degree in solar longitude, merging into the Phoenicids radiant (PHO#254) after λʘ = 225.0°. 2019 observations showed that the Phoenicids were observed between solar longitude 230.4° and 233.7°, based on SonotaCo Network data (Shiba, 2022). The shower parameters as obtained by the GMN method are listed in Table 1.

Figure 4 – The radiant distribution during the solar-longitude interval 218° – 227° in equatorial coordinates.

Figure 5 – The radiant drift.

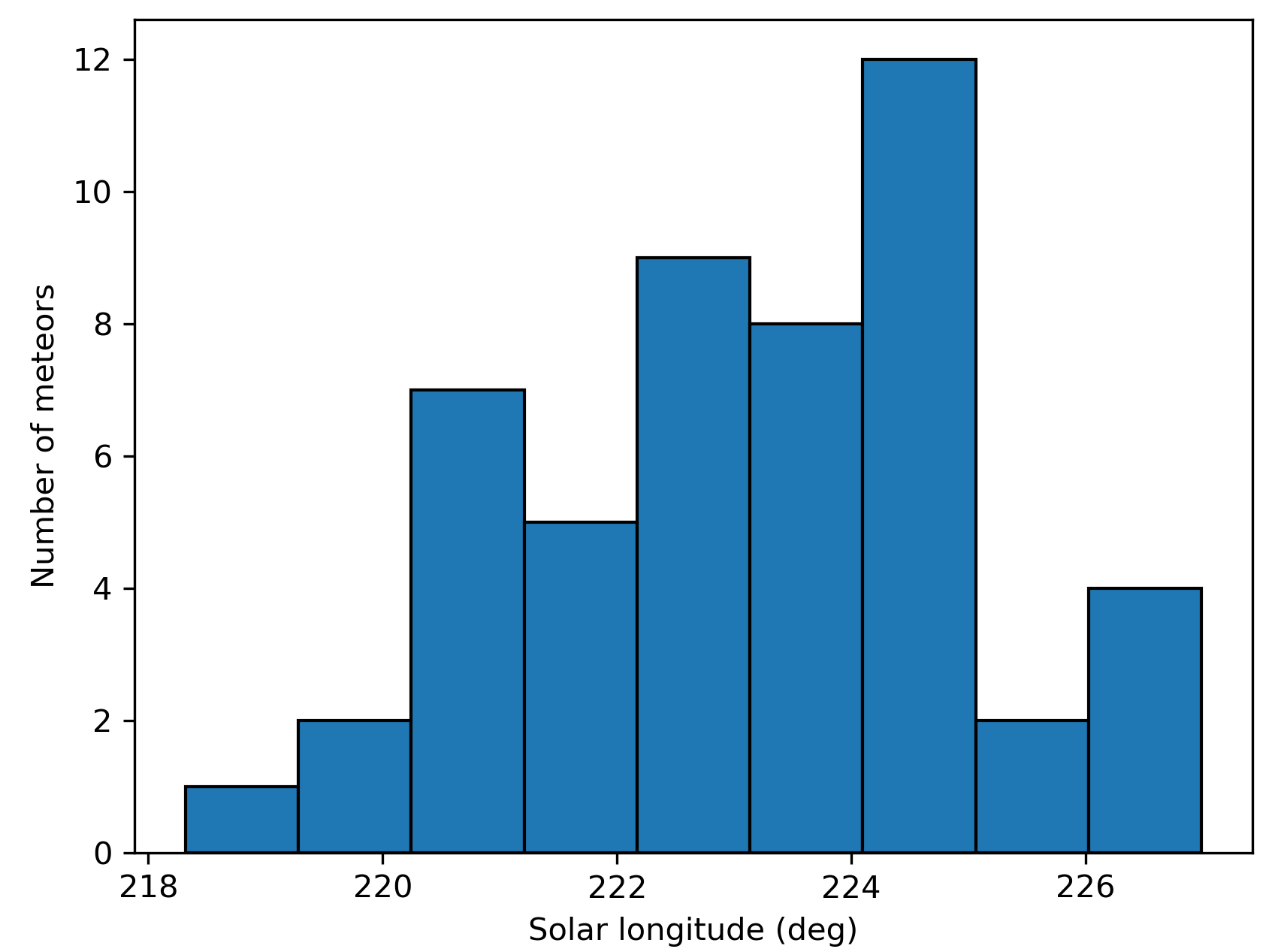

Figure 6 – The uncorrected number of shower meteors recorded per degree in solar longitude.

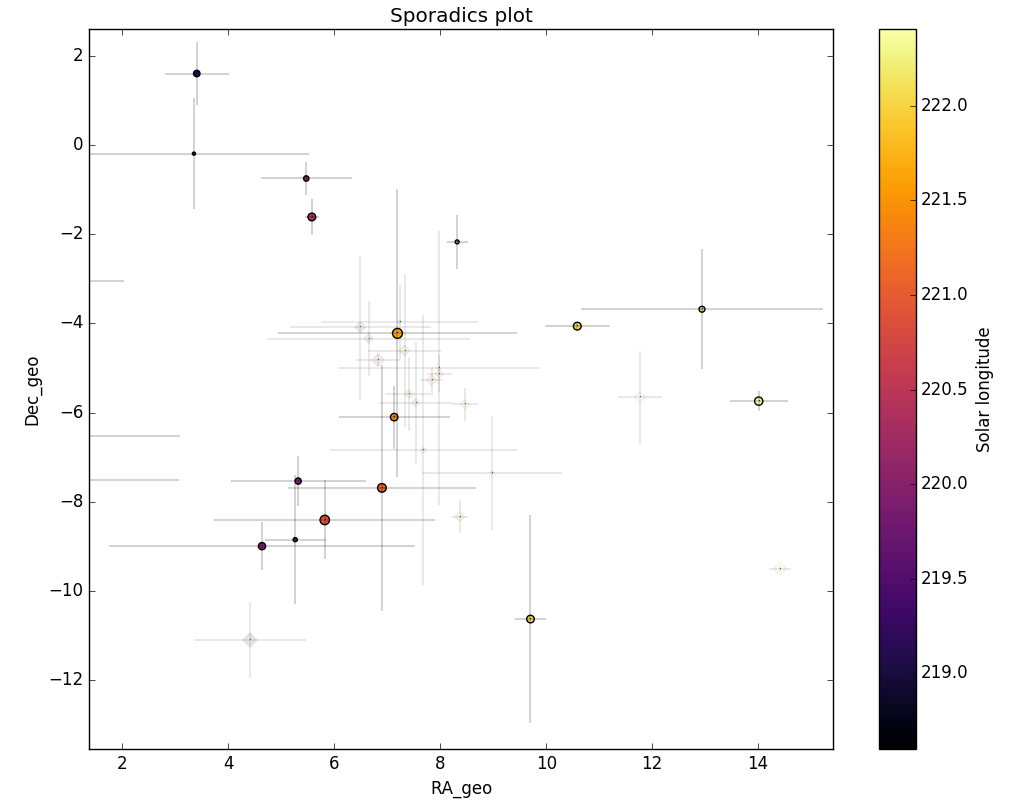

Figure 7 – All non-shower meteor radiants in geocentric equatorial coordinates during the shower activity. The pale diamonds represent the shower radiants plots, error bars represent two sigma values in both coordinates.

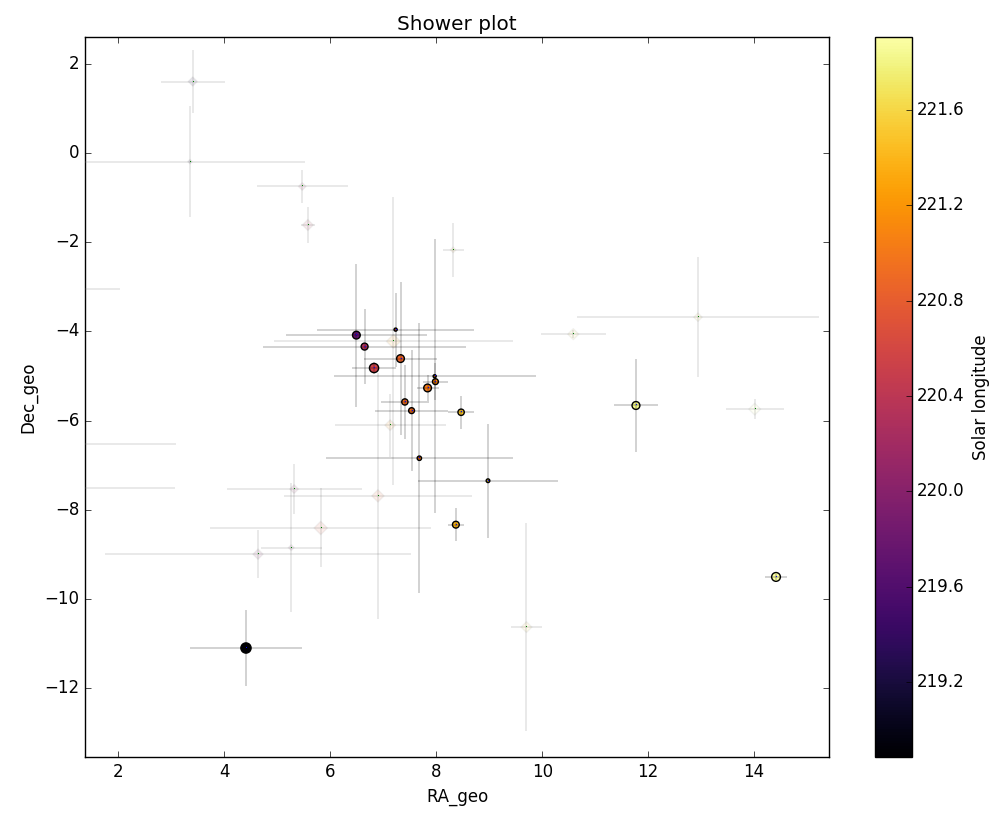

Figure 8 – The reverse of Figure 7, now the shower meteors are shown as circles and the non shower meteors as grayed out diamonds.

The uncorrected raw numbers of shower meteors per degree in solar longitude shows strong fluctuations that are due to the fact that a large number of GMN cameras were hampered by unfavorable weather circumstances during the considered time interval (Figure 6). Figures 7 and 8 show that the 29-Piscids activity appeared on top of the sporadic background noise.

Figure 9 – The radiant distribution during the solar-longitude interval 218° – 227° in Sun centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates.

3 Shower classification based on orbits

Meteor shower identification strongly depends upon the methodology used to select candidate shower members. The sporadic background is almost everywhere present and risks contamination of selections of shower candidates. In order to double check GMN meteor shower detections, another method based on orbit similarity criteria is used. This procedure serves to make sure that no spurious radiant concentrations are mistaken as meteor showers.

A reference orbit is required to start an iterative procedure to approach a mean orbit, which is the most representative orbit for the meteor shower as a whole, removing outliers and sporadic orbits (Roggemans et al., 2019). The mean orbits are computed with the method described by Jopek et al. (2006). Three different discrimination criteria are combined in order to have only those orbits which fit the different criteria thresholds. The D-criteria that we use are these of Southworth and Hawkins (1963), Drummond (1981) and Jopek (1993) combined. Instead of using a single cutoff value for the threshold of the D-criteria, these values are considered in different classes with different thresholds of similarity. Depending upon the dispersion and the type of orbits, the most appropriate threshold of similarity is selected to locate the best fitting mean orbit as the result of an iterative procedure.

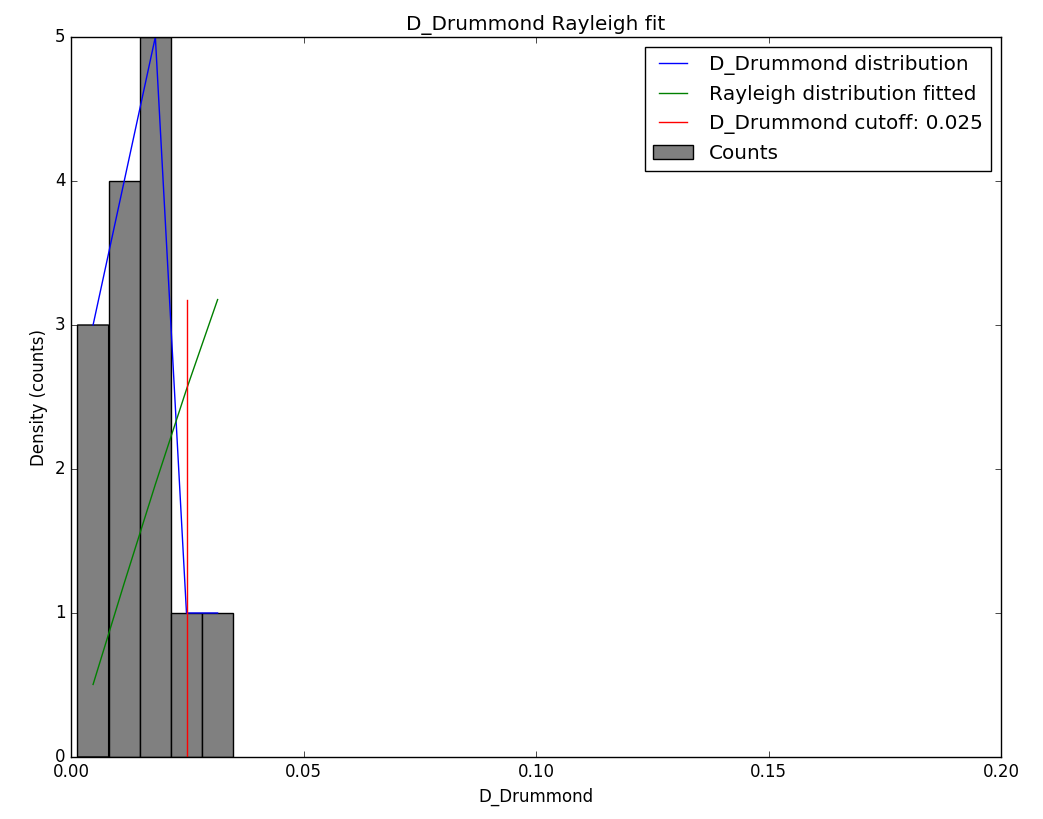

Figure 10 – Rayleigh distribution fit and Drummond DD criterion cutoff.

The Rayleigh distribution fit indicates that a very small cutoff value is required with DD < 0.025 (Figure 10). The use of D-criteria requires caution as the threshold values differ for different types of orbits. Because of the very small cutoff of the threshold values of the D-criteria, only four classes were plotted:

- Medium low: DSH < 0.1 & DD < 0.04 & DJ < 0.1;

- Medium: DSH < 0.075 & DD < 0.03 & DJ < 0.075.

- High: DSH < 0.05 & DD < 0.02 & DJ < 0.05.

- Very high: DSH < 0.025 & DD < 0.01 & DJ < 0.025.

Figure 11 – The radiant distribution during the solar-longitude interval 217° – 228° in equatorial coordinates in 2025, color-coded for different threshold values of the DD orbit similarity criterion.

This method resulted in a mean orbit with 53 related orbits that fit within the similarity thresholds with DSH < 0.075, DD < 0.03 and DJ < 0.075, recorded October 31 – November 9, 2025. The plot of the radiant positions in equatorial coordinates, color-coded for different D-criteria thresholds, has its radiant at 7.8° in Right Ascension and –5.9° in declination (Figure 11). A slightly more tolerant threshold of the D-criteria with DSH < 0.10, DD < 0.04 and DJ < 0.1 results in 65 orbits that fit these threshold values, but with a risk of including contamination with sporadics. Both solutions are mentioned in Table 1.

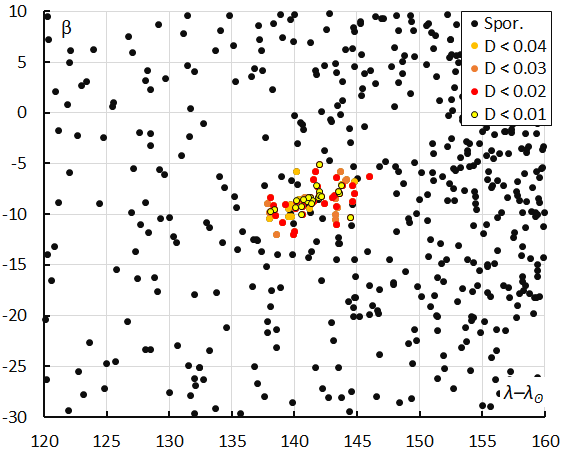

Looking at the Sun-centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates (Figure 12), the radiant appears stretched in Sun-centered longitude due to the strong drift in Sun-centered longitude.

Figure 12 – The radiant distribution during the solar-longitude interval 217° – 228° in Sun-centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates, color-coded for different threshold values of the DD orbit similarity criterion.

Figure 13 – The percentage of PIS-meteors relative to the total number of meteors recorded by cameras. Orange is the result for the GMN shower classification, blue for the D-criteria threshold method.

The uncorrected number of shower meteors recorded per degree in solar longitude in Figure 6 was affected by weather circumstances. Considering the ratio of 29-Piscids meteors to the total number of meteors in 2°-time bins in solar longitude in steps of 0.25° the weather affected fluctuations are largely compensated (Figure 13). The best relative activity rates seem to have occurred at λʘ = 223.5°.

The results obtained from both shower association methods are in good agreement although both methods identified 40 meteors in common with different additional meteors in each sample. Ten 29-Piscids-meteors were identified based on the radiant method but not selected by the orbit method with DSH < 0.075 & DD < 0.03 & DJ < 0.075. 13 orbits were identified as 29-Piscids-orbits but not identified by the radiant based method. Both methods agree on the activity duration.

4 Orbit and parent body

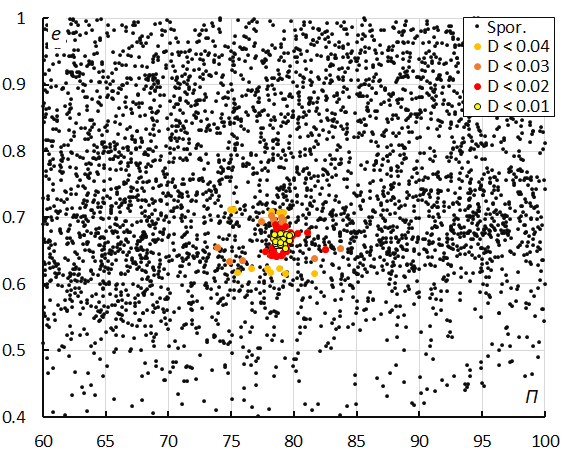

Looking at the diagram of inclination versus longitude of perihelion, we can see a dense concentration (Figure 14). At the same position as the 29-Piscids we find also some meteors classified as Phoenicids but this shower is actually a mis-classification in the IAU-MDC shower list based upon the common parent body of both showers.

Figure 14 – The diagram of the inclination i versus the longitude of perihelion Π color-coded for different classes of D criteria thresholds, for λʘ between 217° and 228°.

Figure 15 – The diagram of the eccentricity e versus the longitude of perihelion Π color-coded for different classes of D criteria thresholds, for λʘ between 217° and 228°.

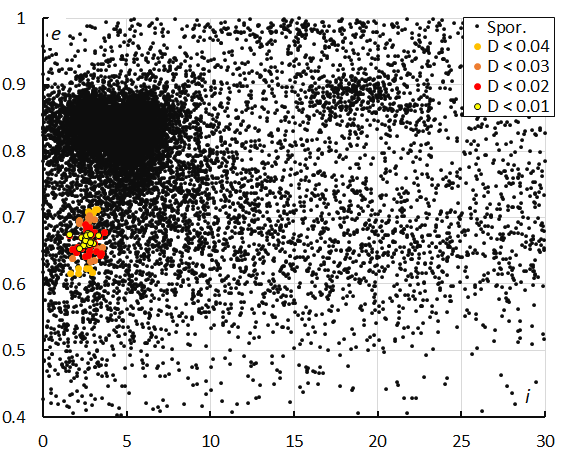

The eccentricity against the longitude of perihelion shows a dense concentration of 29-Piscids (Figure 15). The eccentricity appears also very concentrated against the inclination (Figure 16). This diagram displays some other striking concentrations. The dense cloud visible within 0° < i < 10° and 0.8 < e < 0.9 is the Taurids complex with many delta-Arietids (DAT#631), Southern and Northern Taurids and several other minor showers of the Taurid complex. The concentration within 15° < i < 22° and 0.88 < e < 0.91 is the established shower omicron-Eridanids (OER#338).

Figure 16 – The diagram of the eccentricity e versus the inclination i color-coded for different classes of D criteria thresholds, for λʘ between 217° and 228°.

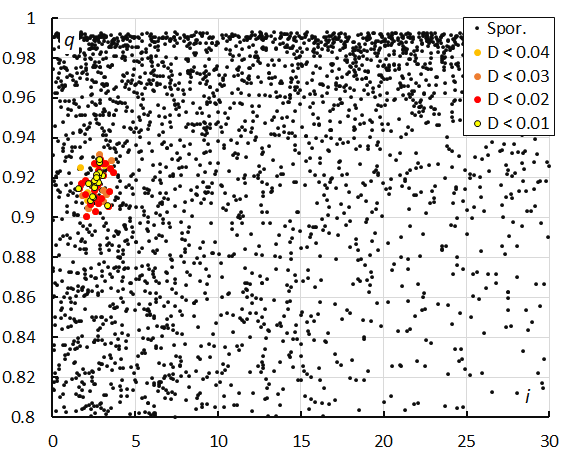

Figure 17 – The diagram of the perihelion distance q versus the inclination i color-coded for different classes of D criteria threshold, for λʘ between 217° and 228°.

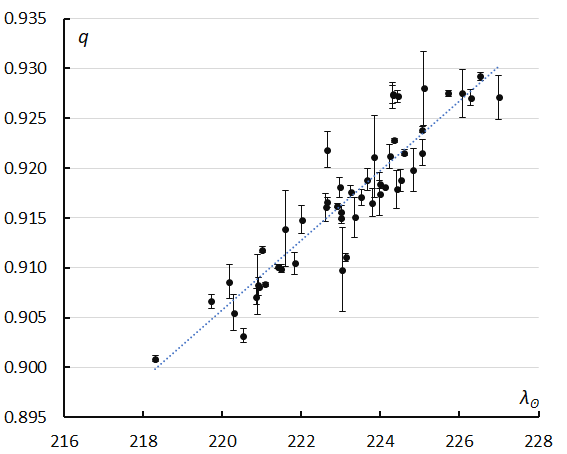

Figure 18 – The evolution of the perihelion distance q in function of the solar longitude λʘ for the 2025 data.

Perihelion distance q versus inclination i appears stretched in perihelion distance (Figure 17). There is a clear trend in perihelion distance in function of time (Figure 18). Applying a simple linear regression this drift referenced to λʘ = 221.0°can be described as: q=0.0035 (λʘ-221.0°)+0.9092

Jenniskens found a similar but slightly different trend of q versus the Node Ω to link the occurrence of the shower activity observed in October 2019 with the activity observed one month later (Jenniskens, 2020).

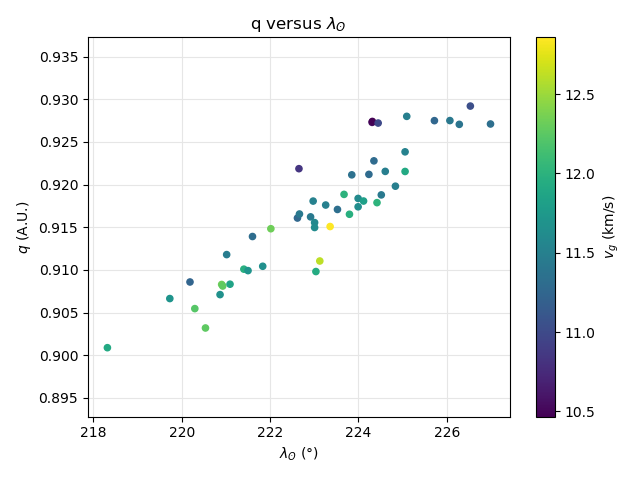

There is also a trend in the geocentric velocity which decreases with time (Figure 19) which can be approached with a linear regression as:vg =-0.0943 ( λʘ-221.0°)+11.817

The increase in perihelion distance q and decrease in geocentric velocity vg has been visualized in Figure 20. If we extrapolate this trend to λʘ = 232.2°, we get q = 0.948 AU and vg = 10.8 km/s, which matches the actually observed values within the uncertainty margins for the data listed under PHO in Table 1. Using λʘ = 204.0° for the October activity reported by CAMS we find q = 0.849 AU and vg = 13.4 km/s, which is slightly different from the observed values but could be explained by the uncertainty on the linear regression extrapolated over two weeks of time.

Figure 19 – The evolution of the geocentric velocity vg in function of the solar longitude λʘ for the 2025 data.

Table 1 – Comparing solutions derived by two different methods, GMN-method based on radiant positions and the orbit association method for DD < 0.04, DD < 0.03 and DD < 0.02 in 2025, CAMS in 2019 (Jennislens, 2023) and the Phoenicids observed by SonotaCo Net (Shiba, 2022).

| 2025 | 2019 | ||||||

| GMN | DD < 0.04 | DD < 0.03 | DD < 0.02 | CAMS-Oct | CAMS-Nov. | PHO | |

| λʘ (°) | 221.0 | 223.3 | 223.3 | 223.5 | 204.0 | 232.0 | 232.2 |

| λʘb (°) | 218.0 | 218.3 | 218.3 | 218.3 | 202.3 | 228.3 | 230.47 |

| λʘe (°) | 228.0 | 227.3 | 227.3 | 227.3 | 205.0 | 235.0 | 233.7 |

| αg (°) | 7.4 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 4.3 | 6.8 | 6.7 |

| δg (°) | –5.3 | –6.0 | –5.9 | –5.9 | –2.7 | –7.6 | –7.7 |

| Δαg (°) | +0.13 | +0.34 | +0.33 | +0.20 | +0.29 | +0.07 | +0.08 |

| Δδg (°) | –0.33 | –0.01 | –0.04 | –0.18 | +0.21 | –0.34 | –0.54 |

| vg (km/s) | 11.8 | 11.5 | 11.5 | 11.5 | 15.4 | 10.5 | 10.9 |

| Hb (km) | 89.6 | 89.4 | 89.5 | 89.6 | – | – | 88.0 |

| He (km) | 77.7 | 77.7 | 77.7 | 77.7 | – | – | 72.8 |

| Hp (km) | 82.4 | 82.2 | 82.2 | 82.2 | – | – | – |

| MagAp | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | – | – | –1.6 |

| λg (°) | 4.66 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 3.07 |

| λg – λʘ (°) | 143.66 | 141.3 | 141.8 | 141.65 | 159.2 | 131.5 | 130.87 |

| βg (°) | –7.79 | –8.7 | –8.6 | –8.6 | –4.3 | –9.5 | –9.73 |

| a (A.U.) | 2.805 | 2.74 | 2.75 | 2.74 | 2.71 | 2.87 | 3.243 |

| q (A.U.) | 0.917 | 0.918 | 0.917 | 0.917 | 0.817 | 0.943 | 0.946 |

| e | 0.673 | 0.665 | 0.667 | 0.665 | 0.697 | 0.671 | 0.708 |

| i (°) | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.65 | 2.6 | 1.89 | 2.69 | 2.7 |

| ω (°) | 35.4 | 35.4 | 35.6 | 35.6 | 55.3 | 27.0 | 26.6 |

| Ω (°) | 43.3 | 43.3 | 43.3 | 43.5 | 23.9 | 52.0 | 52.2 |

| Π (°) | 78.7 | 78.7 | 78.9 | 79.1 | 79.2 | 78.8 | 78.8 |

| Tj | 2.94 | 2.98 | 2.97 | 2.98 | 3.00 | 2.92 | 2.72 |

| N | 50 | 65 | 53 | 41 | 40 | 107 | 9 |

Figure 20 – The diagram of the perihelion distance q against the solar longitude λʘ, color-coded in function of the geocentric velocity vg for the 2025 data.

Figure 21 – Comparing the GMN solution for the 29-Piscids (blue), the solutions obtained by CAMS October 2019 and November 2019 and the solution for the Phoenicids 2019 by SonotaCo Net, close-up at the inner Solar System. (Plotted with the Orbit visualization app provided by Pető Zsolt).

The Tisserand’s parameter relative to Jupiter, Tj (= 2.94), identifies the orbit as of a Jupiter Family Comet type orbit. Figure 21 compares the orbits obtained in 2025 by GMN with those obtained by CAMS and SonotaCo Net in 2019. The meteoroid stream encounters the Earth at its descending node. The orbits are parallel and caused by dust trails from a common origin.

A parent-body search of the top 10 results in candidates with a threshold for the Drummond DD criterion value lower than 0.035 (Table 2). Asteroid 2022 UX20 with DD < 0.006 looks like the most plausible candidate but orbit integrations are required to assess if there is a relationship. However, the most likely parent maybe 289P/Blanpain, a lost comet supposed to have disintegrated into multiple fragments and dust.

Minor planet 2003 WY25 turned out to be in an orbit very similar to that of the lost comet D/1819 W1 (Blanpain) integrated forward in time and might be a remnant of comet D/1819 W1 (Blanpain). This comet was discovered on 1819 November 28, when it was unusually close to Earth. About 13 observations were made at Paris, Bologna, and Milan from 1819 December 14 to 1820 January 15, but the comet was then lost. Esko Lyytinen integrated the orbit of 2003WY25 back to 1819 and again forward for a range of orbits to confirm that the dust encountered Earth in December 1956 when the Phoenicids outburst was observed. Other years with possible activity caused by debris from D/Blanpain were predicted for 2019, 2034, 2039 and 2044, but not 2025 (Jenniskens and Lyytinen, 2005).

2003WY25 does not appear within the top ten matches, but 289P/Blanpain does. The other objects are all very faint and discovered after 2003WY25, with very similar orbits and may be remnants of 289P/Blanpain just like 2003WY25.

Table 2 – Top ten matches of a search for possible parent bodies with DD < 0.035

| Name | DD |

| 2022 UX20 | 0.006 |

| 2021 VQ6 | 0.02 |

| 2019 VD | 0.024 |

| 2024 VE | 0.028 |

| 2024 TX4 | 0.028 |

| 2022 CG2 | 0.03 |

| 289P/Blanpain | 0.032 |

| 2014 UA8 | 0.032 |

| 2022 BR1 | 0.033 |

| 2021 AY2 | 0.033 |

5 Past years’ activity

A detailed overview of past Phoenicid activity has been published in Roggemans et al. (2020) and Jenniskens and Lyytinen (2005).

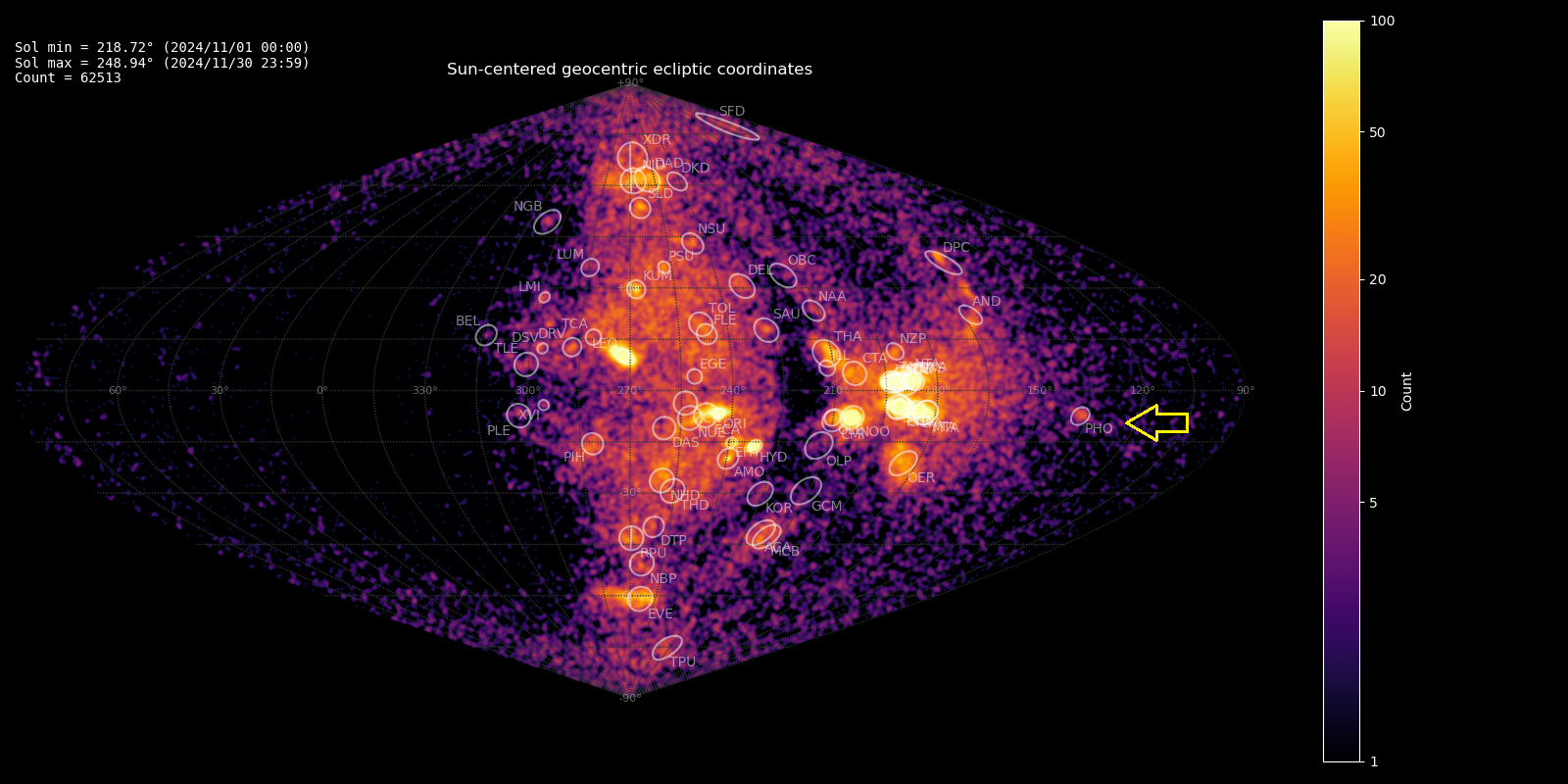

Checking past years’ meteor orbit data in the GMN orbit datasets, the 29-Piscids turned out to have produced better activity in 2024 than in 2025 when less cameras recorded these meteors. Most meteors were identified as PHO#254 in 2024 but the shower got no specific attention (Figure 25). 100 orbits were recorded that fit the D-criteria thresholds with DSH < 0.075 & DD < 0.03 & DJ < 0.075 in 2024. Each previous year a number of orbits fitted these criteria, indicating an annual activity although very weak. A search in previous years yield 25 orbits in 2023, 17 in 2022, 20 in 2021, 7 in 2020 and 28 in 2019 (Figure 26).

For other networks the orbit datasets were searched with slightly more tolerant D-criteria thresholds DSH < 0.1 & DD < 0.04 & DJ < 0.1 which surely risk to include some sporadic contamination. Using these criteria CAMS had the following numbers per year: 2010 (3), 2011 (6), 2012 (1), 2013 (14), 2014 (15), 2015 (13) and 2016 (17). SonotaCo Net had: 2008 (1), 2009 (2), 2010 (1), 2011 (0), 2012 (0), 2013 (4), 2014 (0), 2015 (2), 2016 (1), 2017 (1), 2018 (3), 2019 (7), 2020 (2), 2021 (7), 2022 (8), 2023 (2), 2024 (9). EDMOND had: 2007 (1), 2008 (1), 2009 (0), 2010 (2), 2011 (4), 2012 (3), 2013 (3), 2014 (3), 2015 (3), 2016 (6), 2017 (1), 2018 (3), 2019 (7), 2020 (4), 2021 (1), 2022 (1), 2023 (1).

Table 3 – Comparing solutions for 2024 and 2019 derived by two different methods, GMN-method based on radiant positions and orbit association for DD < 0.03.

| 2024 | 2019 | |||

| GMN | DD < 0.03 | GMN | DD < 0.03 | |

| λʘ (°) | 226.0 | 226.7 | 231.0 | 231.3 |

| λʘb (°) | 212.0 | 212.3 | 219.0 | 219.2 |

| λʘe (°) | 238.0 | 237.8 | 238.0 | 238.3 |

| αg (°) | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.6 |

| δg (°) | –5.7 | –5.7 | –7.7 | –7.7 |

| Δαg (°) | +0.07 | +0.06 | +0.16 | +0.18 |

| Δδg (°) | –0.10 | –0.10 | –0.27 | –0.07 |

| vg (km/s) | 10.8 | 10.96 | 10.3 | 10.3 |

| Hb (km) | 88.9 | 89.2 | 89.6 | 89.6 |

| He (km) | 77.1 | 78.0 | 78.7 | 78.4 |

| Hp (km) | 81.6 | 82.3 | 82.8 | 82.4 |

| MagAp | +0.8 | +0.7 | +1.1 | +1.0 |

| λg (°) | 3.74 | 3.9 | 2.86 | 3.2 |

| λg – λʘ (°) | 137.74 | 137.2 | 131.86 | 131.8 |

| βg (°) | –7.8 | –7.7 | –9.62 | –9.5 |

| a (A.U.) | 2.674 | 2.77 | 2.768 | 2.79 |

| q (A.U.) | 0.930 | 0.926 | 0.946 | 0.945 |

| e | 0.652 | 0.665 | 0.658 | 0.661 |

| i (°) | 2.2 | 2.25 | 2.6 | 2.55 |

| ω (°) | 32.0 | 32.7 | 26.7 | 27.3 |

| Ω (°) | 46.4 | 45.8 | 51.7 | 51.4 |

| Π (°) | 78.4 | 78.5 | 78.5 | 78.7 |

| Tj | 3.03 | 2.97 | 2.98 | 2.96 |

| N | 104 | 91 | 29 | 25 |

Applying the iterative procedure to derive the best fitting mean orbit nine of the hundred orbits of 2024 were filtered out as outliers, for 2019 three of the 28 orbits were rejected as outliers. The resulting mean orbit parameters have been summarized in Table 3 compared with the GMN radiant classification method.

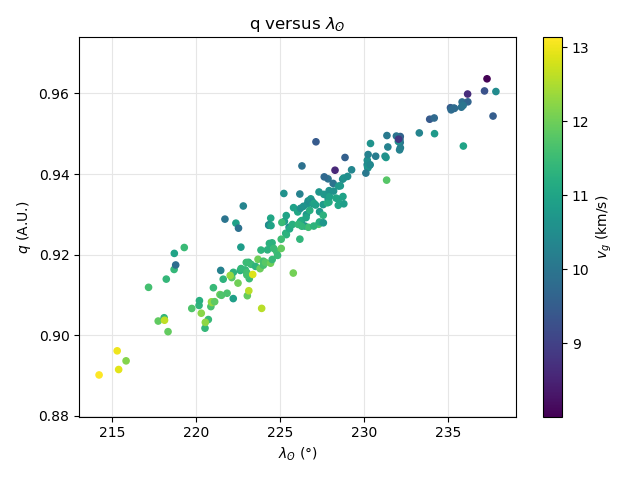

Figure 22 shows the trend of the increasing perihelion distance q in function of time, using the data of 2019, 2024 and 2025 combined based on orbit classification. The trend for q and vg in 2024 referenced to λʘ = 226.7°can be described by the following equations:

q=0.0031 (λʘ-226.7°)+0.9298

vg=-0.1162 ( λʘ-226.7°)+10.989

Figure 23 shows the trend of the decreasing geocentric velocity. In 2024 the shower activity lasted longer than in 2025 and in 2019 the shower displayed its activity a bit later than in 2025. Combining all 29-Piscids identified with the GMN radiant association method, the trend in increasing perihelion distance and decreasing velocity is very clear in Figure 24. It is obvious that the recorded orbits in 2019, 2024 and 2025 all belong to the same meteoroid stream 29-Piscids and should be identified as PIS#1046 because of the very different radiant position obtained for the Phoenicids outburst observed in 1956 and identified as PHO#254.

Figure 22 – The evolution of the perihelion distance q in function of the solar longitude λʘ.

Figure 23 – The evolution of the geocentric velocity vg in function of the solar longitude λʘ.

Figure 24 – The diagram of the perihelion distance q against the solar longitude λʘ, color-coded in function of the geocentric velocity vg for the 2019, 2024 and 2025 data combined.

Figure 25 – Radiant density map (sinusoidal projection) with 62513 radiants obtained by the Global Meteor Network during November, 2024. The position of the 29-Piscids in Sun-centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates is marked with a yellow arrow.

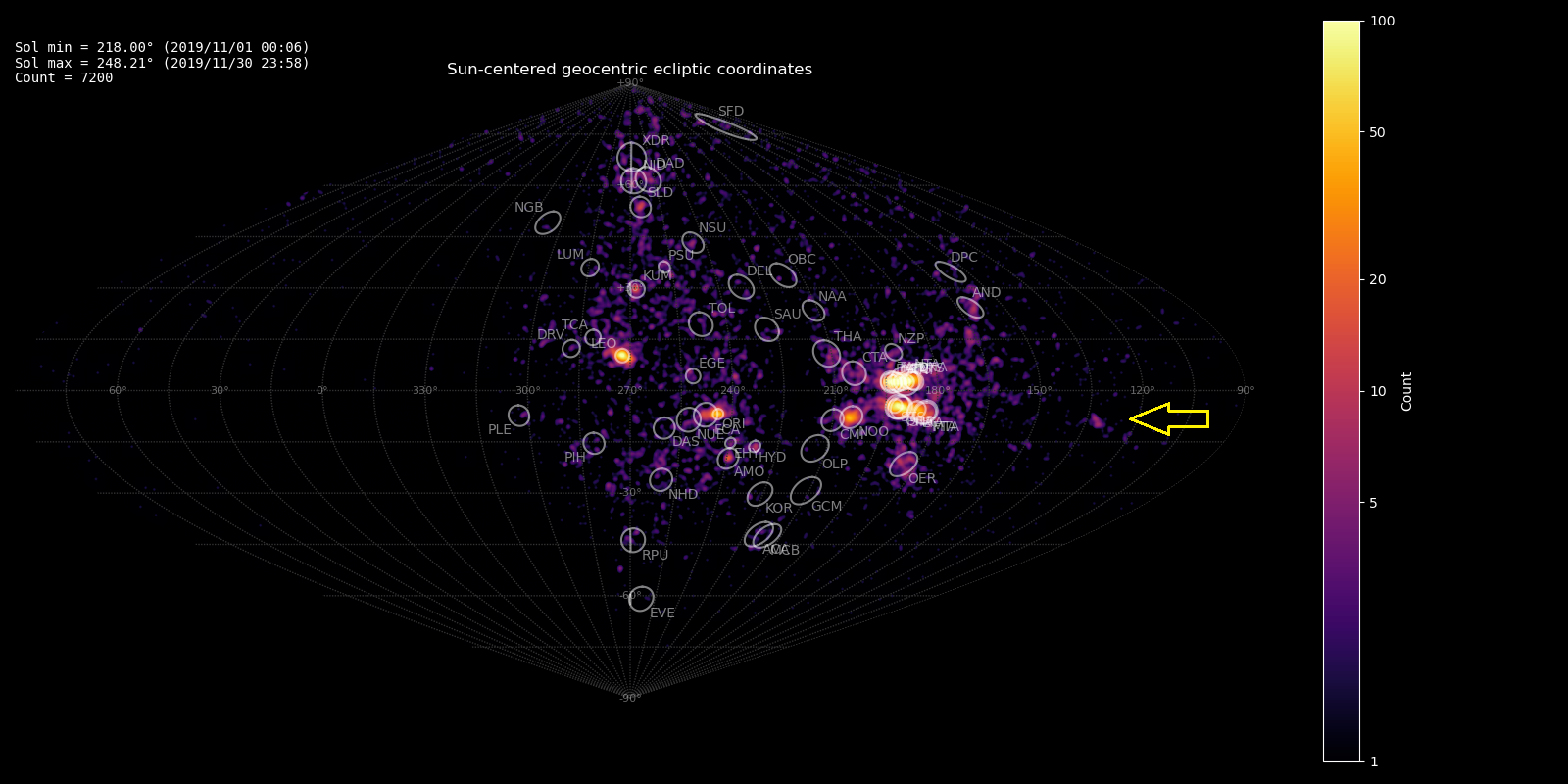

Figure 26 – Radiant density map (sinusoidal projection) with 7200 radiants obtained by the Global Meteor Network during November, 2019. The position of the 29-Piscids in Sun-centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates is marked with a yellow arrow.

6 Conclusion

The observed enhanced activity of the 29-Piscids in 2025 confirms the existence of this shower. More evidence has been found in the GMN dataset as this shower displayed enhanced activity in 2024 and 2019 too. Most of the orbits recorded in 2024 were classified as Phoenicids (PHO#254) although these matches perfectly with the 29-Piscids. The confusion arises from the erroneous inclusion of a 2019 entry in the IAU-MDC Working List of Meteor Showers listed under the Phoenicids, which originally concerned only the 1956 outburst with a radiant in the constellation Phoenix. The 2019 entry listed under Phoenicids is another solution for the activity listed under 29-Piscids and should be moved under this shower entity. Both showers likely have the same parent body, the disintegrated comet 289P/Blanpain. Some of the matching candidate parent bodies may actually be remnants of the broken-up comet. Esko Lyytinen computed that planetary perturbations with Jupiter caused the orbital node to shift to smaller values, as a result of which the annual shower now peaks earlier than the 1956 Phoenicid outburst (Jenniskens and Lyytinen, 2025). Mikiya Sato and Jun-ichi Watanabe found that the orbit of some dust trails released by 289P/Blanpain changed a lot by perturbations, so that the Earth approached the dust at the beginning of November, almost one month earlier than in 1956. In 2008 a theoretical radiant was calculated as R.A. = 7.0° and Decl. = –5.5° far north of the position of the Phoenicids in 1956. (Sato and Watanabe, 2010). This position as well as the time predicted for the best activity (8 November) fit with the 29-Piscids radiant as observed in recent years. Sato and Watanabe (2014) confirmed activity recorded by SonotaCo Net in 2008 but no details about radiant or velocity were mentioned. They identified this activity as Phoenicids although the radiant position is far away from the 1956 position. The 2019 activity had been predicted but the time and radiant position differed from the actually observed outburst. Nothing was expected for 2024–2025 with enhanced activity of this episodic shower, other years showed only some weak annual activity.

Future studies and observations may help to unravel the remnants of the broken-up comet 289P/Blanpain with its dust trails and possible larger fragments such as minor planet 2003 WY25, which is probably not the only surviving large piece. The actual 2019, 2024–2025 observations of the 29-Piscids may help stream modelers to adjust the model to fit the observed results.

Acknowledgments

This report is based on the data of the Global Meteor Network (Vida et al., 2020a; 2020b; 2021) which is released under the CC BY 4.0 license. We thank all 825 participants in the Global Meteor Network project for their contribution and perseverance. A list with the names of the volunteers who contribute to GMN has been published in the 2024 annual report (Roggemans et al., 2025). The following 360 cameras recorded 29 Piscid meteors used for the 2019, 2024 and 2025 meteor shower data: AT0002, AT0004, AU0002, AU000A, AU000C, AU000D, AU000F, AU000S, AU000T, AU000V, AU000W, AU000X, AU000Y, AU0010, AU001A, AU001B, AU001E, AU001F, AU001K, AU001L, AU001P, AU001R, AU001S, AU001U, AU001V, AU001W, AU001X, AU001Y, AU001Z, AU0029, AU002A, AU0030, AU003E, AU003G, AU003J, AU0041, AU0047, AU0048, AU004B, AU004J, AU004K, BA0003, BA0005, BE0005, BE0007, BE000K, BE000P, BE000Q, BG0001, BG0002, BG0003, BG000B, BG000D, BG000K, BR000F, BR000S, BR000T, BR0015, BR001G, BR001W, BR002A, CA0005, CA000R, CA0012, CA001N, CA001R, CA0022, CA0023, CA002R, CA0031, CA0032, CH0002, CH0003, CZ0004, CZ000C, CZ000E, CZ000K, CZ000L, CZ000M, DE0001, DE0002, DE0004, DE000B, DE000K, DE000Q, DE000W, DE000X, DE0013, ES0001, ES000H, FR000A, FR000Y, FR000Z, FR0016, GR0002, GR0004, GR0005, GR0006, GR0009, HR0006, HR0008, HR000D, HR000K, HR000P, HR000Q, HR000R, HR000S, HR000W, HR0015, HR001J, HR001R, HR001X, HR001Z, HR0024, HR002D, HR002E, HR002F, HR002X, HR002Y, HU0001, HU0002, HU0003, KR0002, KR0009, KR000A, KR000B, KR000D, KR000H, KR000J, KR000P, KR0019, KR001S, KR0021, KR0023, KR0024, KR0027, KR0028, KR002C, KR002F, KR002G, KR002S, KR003A, KR003H, KR003J, KR003K, KR003L, KR003Q, KR003R, KR003S, KR003W, NL000C, NL000P, NL000Q, NL000T, NL000U, NL0010, NZ0001, NZ0003, NZ0004, NZ0007, NZ0009, NZ000B, NZ000D, NZ000G, NZ000N, NZ000R, NZ000V, NZ000X, NZ000Z, NZ0017, NZ0018, NZ0019, NZ001C, NZ001G, NZ001P, NZ001R, NZ001Z, NZ0022, NZ0023, NZ0026, NZ0027, NZ0029, NZ002C, NZ002D, NZ002E, NZ002G, NZ002K, NZ002L, NZ002N, NZ002P, NZ002Q, NZ002R, NZ002S, NZ002T, NZ002V, NZ002W, NZ002X, NZ002Y, NZ002Z, NZ0030, NZ0032, NZ0033, NZ0034, NZ0035, NZ0036, NZ0037, NZ003A, NZ003B, NZ003C, NZ003E, NZ003H, NZ003K, NZ003N, NZ003Q, NZ003S, NZ003T, NZ003U, NZ003W, NZ003Y, NZ0042, NZ0046, NZ0049, NZ004A, NZ004B, NZ004C, NZ004D, NZ004E, NZ004H, NZ004J, NZ004L, NZ004N, NZ004R, NZ0051, NZ0059, NZ005A, NZ005C, NZ005D, NZ005G, NZ005H, NZ005L, NZ005Y, NZ005Z, RO0001, RO0002, SI0002, SI0006, SK0006, UA0001, UA0002, UK0004, UK0006, UK000D, UK000F, UK001Z, UK0031, UK0055, UK005J, UK0061, UK0066, UK006P, UK0080, UK0092, UK0096, UK009D, UK009Q, UK009X, UK00A4, UK00A5, UK00AD, UK00B0, UK00B1, UK00B7, UK00BA, UK00BK, UK00BN, UK00BW, UK00CA, UK00CC, UK00CS, UK00CT, UK00D6, US0001, US0002, US0003, US0004, US0005, US0006, US0007, US0008, US0009, US000A, US000C, US000D, US000E, US000G, US000H, US000J, US000K, US000L, US000M, US000P, US000R, US000S, US000U, US001E, US001L, US001P, US001V, US0020, US0021, US0023, US002P, US002R, US002W, US0035, US0038, US003M, US003N, US003R, US003T, US0046, US004B, US004C, US004J, US004P, US004Q, US0051, US005D, US005E, US005F, US005J, US005X, US005Y, US005Z, USL004, USL007, USL009, USL00A, USL00B, USL00F, USL00J, USL00L, USL00M, USL00N, USL00Q, USL012, USL014, USL018, USL01E, USN001, USV001, USV002, USV003, ZA0001, ZA0006, ZA0007, ZA0008, ZA0009, ZA000C.

References

Drummond J. D. (1981). “A test of comet and meteor shower associations”. Icarus, 45, 545–553.

Jenniskens P. and Lyytinen E. (2005). “Meteor showers from the debris of broken comets: D/1819 W1 (Blanpain), 2003 WY25, and the Phoenicids”. The Astronomical Journal, 130, 1286–1290.

Jenniskens P. (2020). “29 Piscids (PIS#1046) meteor shower 2019”. eMetN Meteor Journal, 5, 370–371.

Jenniskens P. (2023). Atlas of Earth’s meteor showers. Elsevier, Cambridge, United states. ISBN 978-0-443-23577-1. Page 477.

Jopek T. J. (1993). “Remarks on the meteor orbital similarity D-criterion”. Icarus, 106, 603–607.

Jopek T. J., Rudawska R. and Pretka-Ziomek H. (2006). “Calculation of the mean orbit of a meteoroid stream”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 371, 1367–1372.

Moorhead A. V., Clements T. D., Vida D. (2020). “Realistic gravitational focusing of meteoroid streams”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 494, 2982–2994.

Roggemans P., Johannink C. and Campbell-Burns P. (2019). “October Ursae Majorids (OCU#333)”. eMetN Meteor Journal, 4, 55–64.

Roggemans P., Johannink C. and Martin P. (2020). “Phoenicids (PHO#254) activity in 2019”. eMetN Meteor Journal, 5, 4–10.

Roggemans P., Campbell-Burns P., Kalina M., McIntyre M., Scott J. M., Šegon D., Vida D. (2025). “Global Meteor Network report 2024”. eMetN Meteor Journal, 10, 67–101.

Sato M, Watanabe J. (2010). “Forecast for Phoenicids in 2008, 2014, and 2019”. Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan, 62, 509–513.

Sato M., Watanabe J. (2014). “Correction effect to the radiant dispersion in case of low velocity meteor showers”. In Jopek T. J., Rietmeijer F. J. M., Watanabe J., Williams I. P., editors, Proceedings of the Meteoroids 2013 Conference, Poznań, Poland, Aug. 26-30, 2013. A.M. University, pages 329–333.

Shiba Y. (2022). “Jupiter Family Meteor Showers by SonotaCo Network Observations”. WGN, Journal of the International Meteor Organization, 50, 38–61.

Southworth R. B. and Hawkins G. S. (1963). “Statistics of meteor streams”. Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics, 7, 261–285.

Vida D., Gural P., Brown P., Campbell-Brown M., Wiegert P. (2020a). “Estimating trajectories of meteors: an observational Monte Carlo approach – I. Theory”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 491, 2688–2705.

Vida D., Gural P., Brown P., Campbell-Brown M., Wiegert P. (2020b). “Estimating trajectories of meteors: an observational Monte Carlo approach – II. Results”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 491, 3996–4011.

Vida D., Šegon D., Gural P. S., Brown P. G., McIntyre M. J. M., Dijkema T. J., Pavletić L., Kukić P., Mazur M. J., Eschman P., Roggemans P., Merlak A., Zubrović D. (2021). “The Global Meteor Network – Methodology and first results”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 506, 5046–5074.