By Damir Šegon, Denis Vida, Paul Roggemans, James M. Scott, Jeff Wood

Abstract: A meteor shower on a Long-Period Comet type orbit (TJ = –0.16) was detected during October 28 – November 4, 2025, by the Global Meteor Network. 57 meteors belonging to the new shower were observed between 215° < λʘ < 222° from a radiant at R.A. = 99.45° and Decl.= +6.95° in the constellation of Monoceros, with a geocentric velocity of 62.32 km/s. The new meteor shower has been listed in the IAU MDC Working List of Meteor Showers under the temporary name-designation: M2025-V1.

1 Introduction

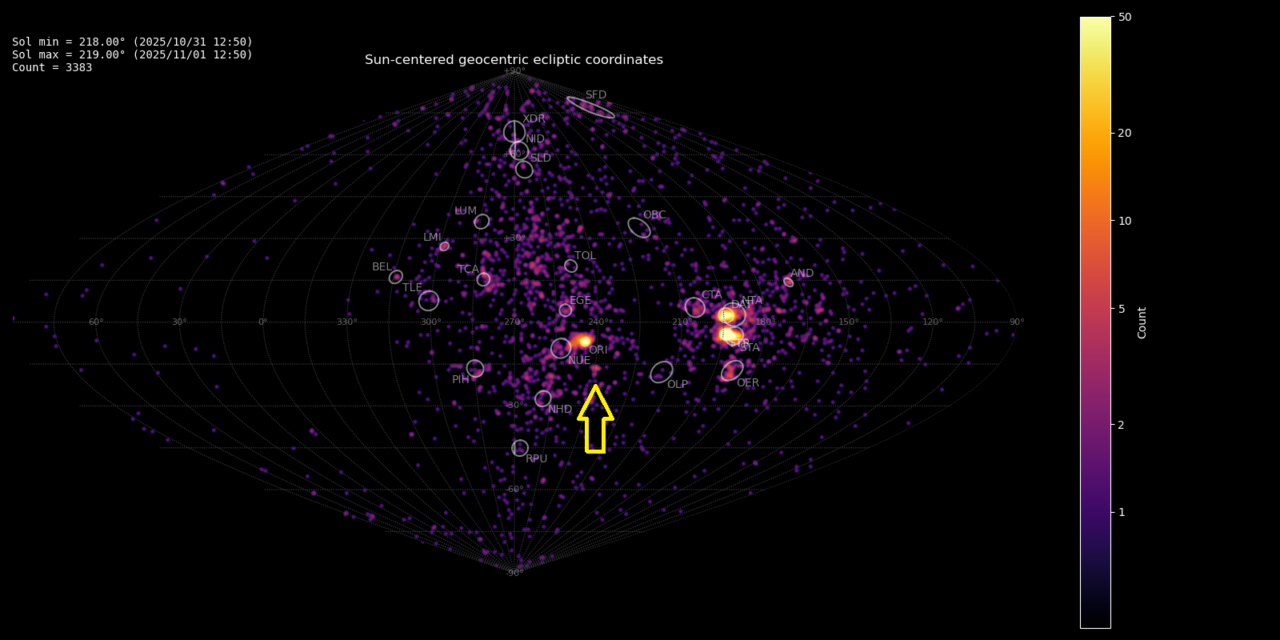

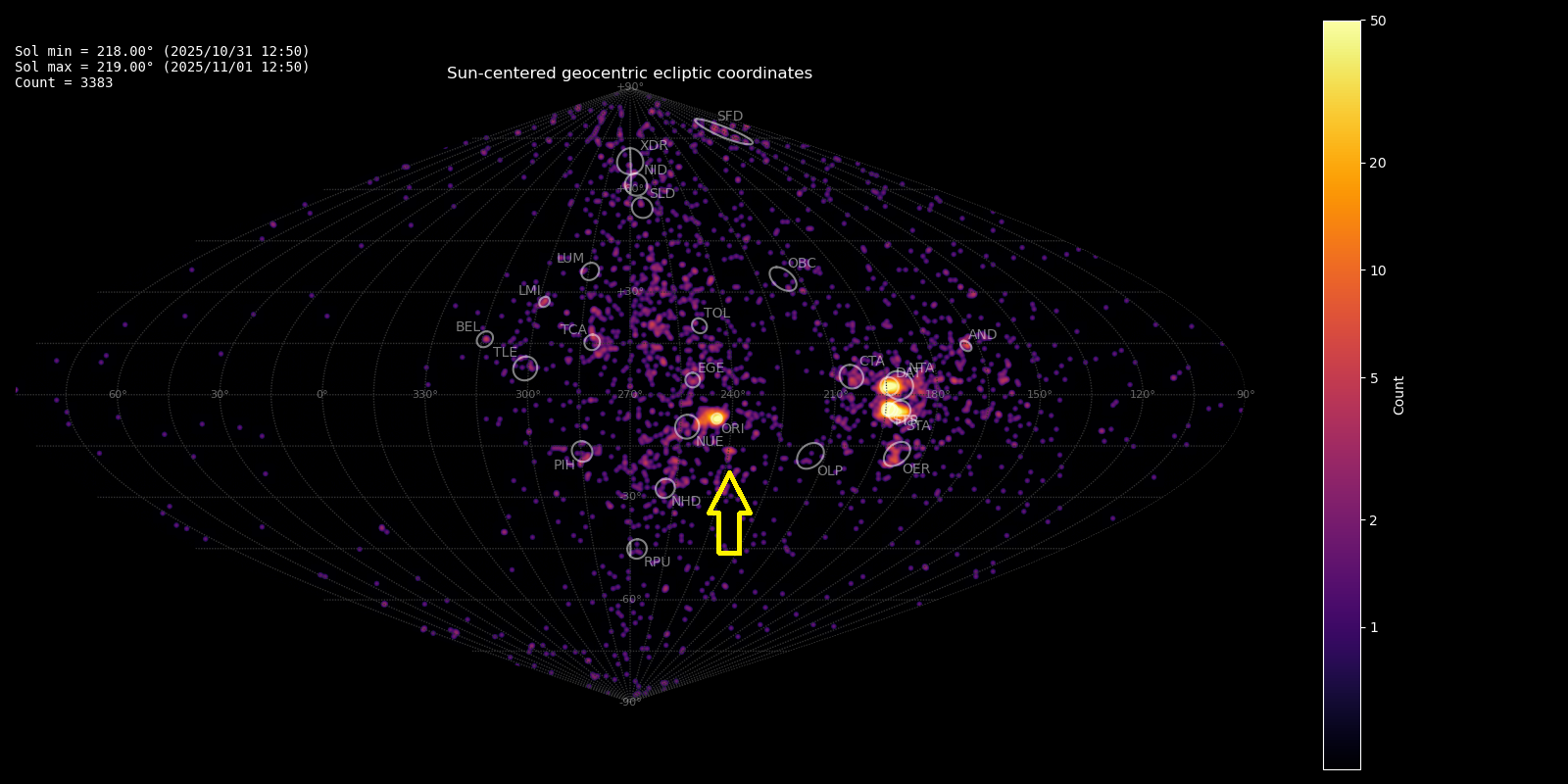

The GMN radiant maps from October 28 until November 4, 2025 showed a clear concentration of related radiants in the constellation of Monoceros. The activity lasted one week with an almost constant level of activity with the radiant well visible on the radiant density maps see Figure 1. When the activity had ceased, 57 meteors of this new meteor shower had been registered by the Global Meteor Network low-light video cameras. The shower was independently observed by 214 cameras in Australia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, France, Greece, Hungary, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea, Ukraine, United Kingdom and the United States.

Figure 1 – Radiant density map in sinusoidal projection with 3383 radiants obtained by the Global Meteor Network during October 31 – November 1, 2025. A distinct concentration is visible in Sun-centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates which was identified as a new meteor shower with the temporary identification M2025-V1. Activity from this new source was detected during an entire week.

2 Shower classification based on radiants

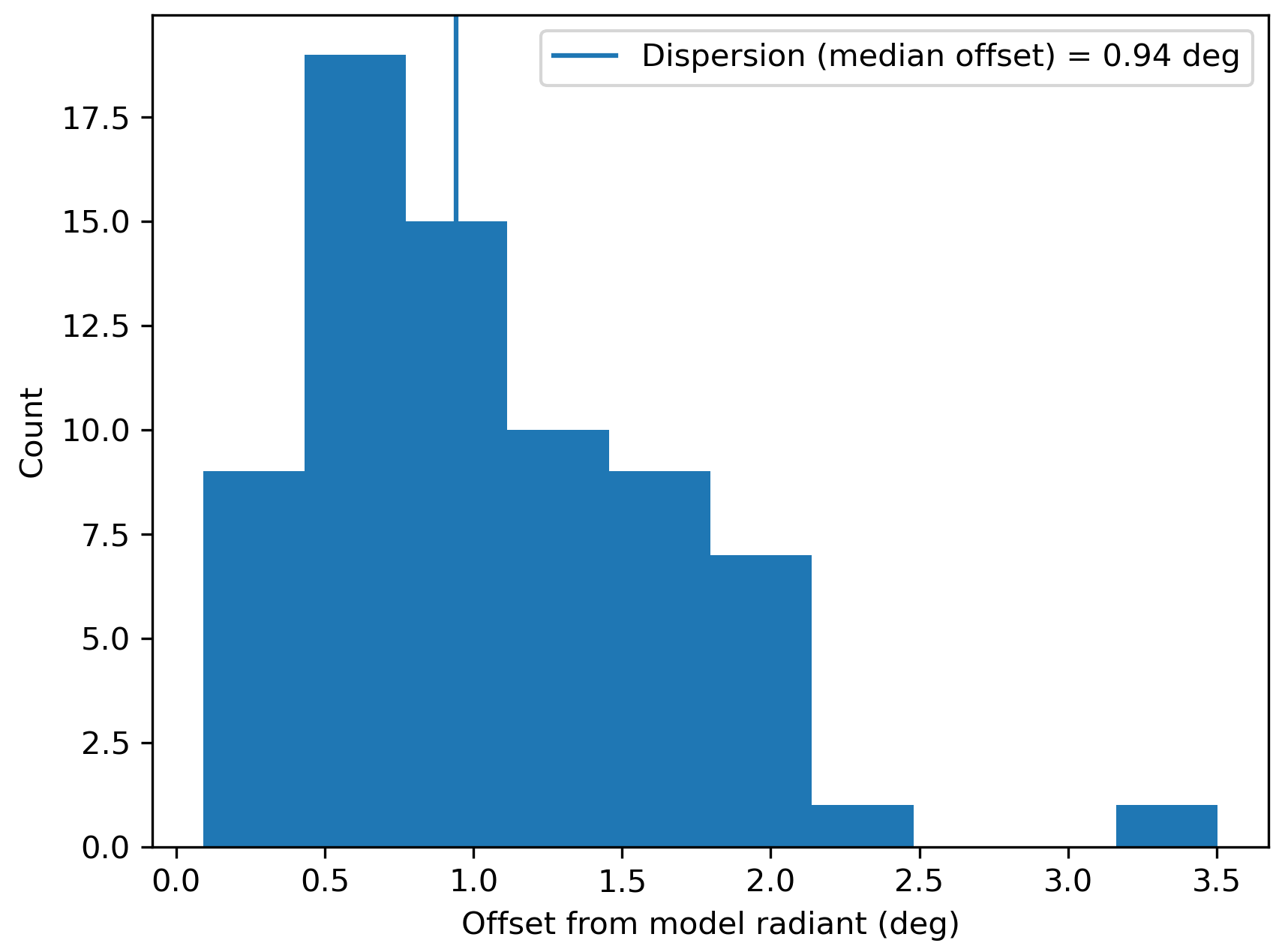

The GMN shower association criteria assume that meteors within 1° in solar longitude, within 2.2° in radiant in this case, and within 10% in geocentric velocity of a shower reference location are members of that shower. Further details about the shower association are explained in Moorhead et al. (2020).

Figure 2 – Dispersion median offset on the radiant position.

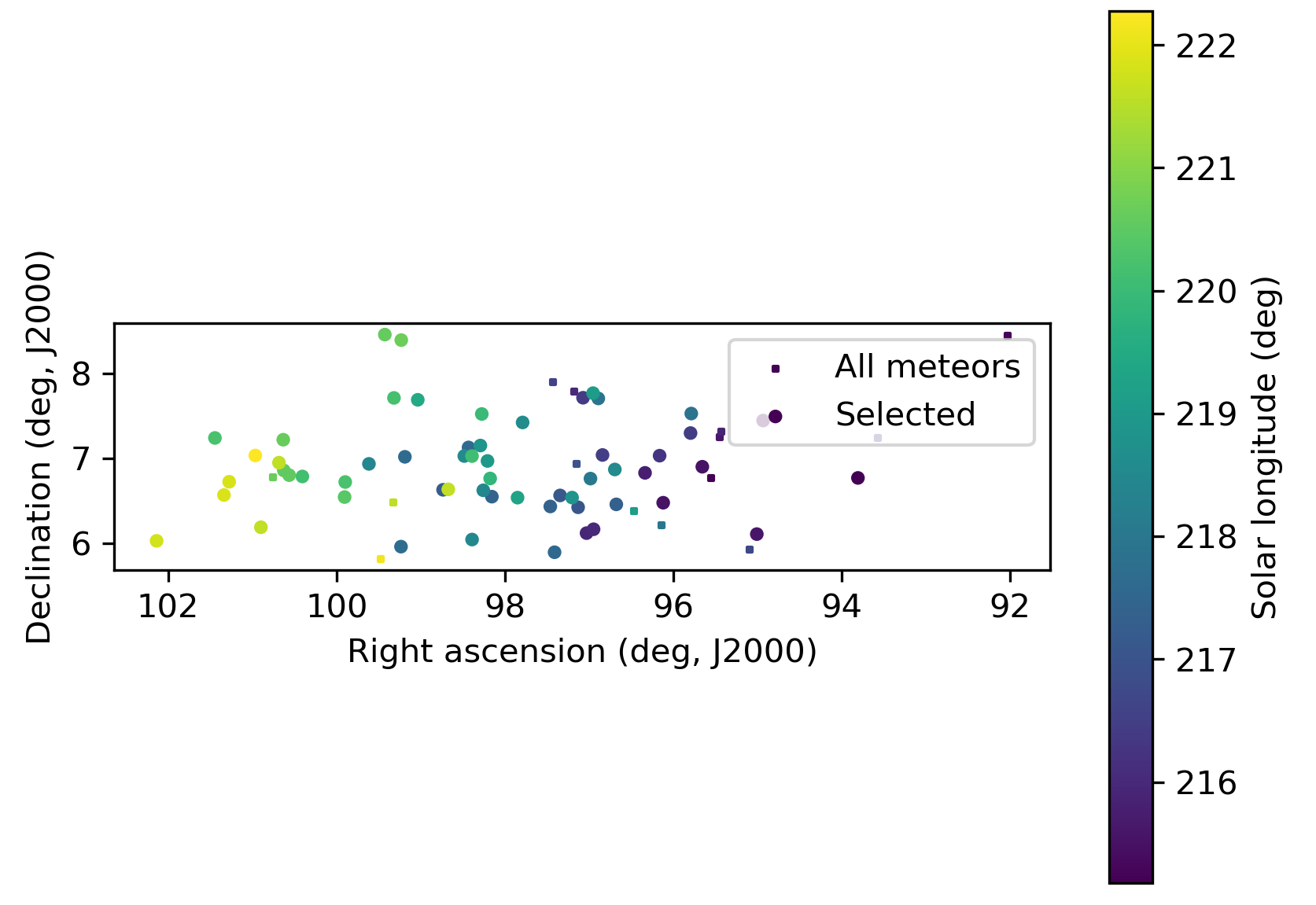

Figure 3 – The radiant distribution during the solar-longitude interval 215° – 222° in equatorial coordinates.

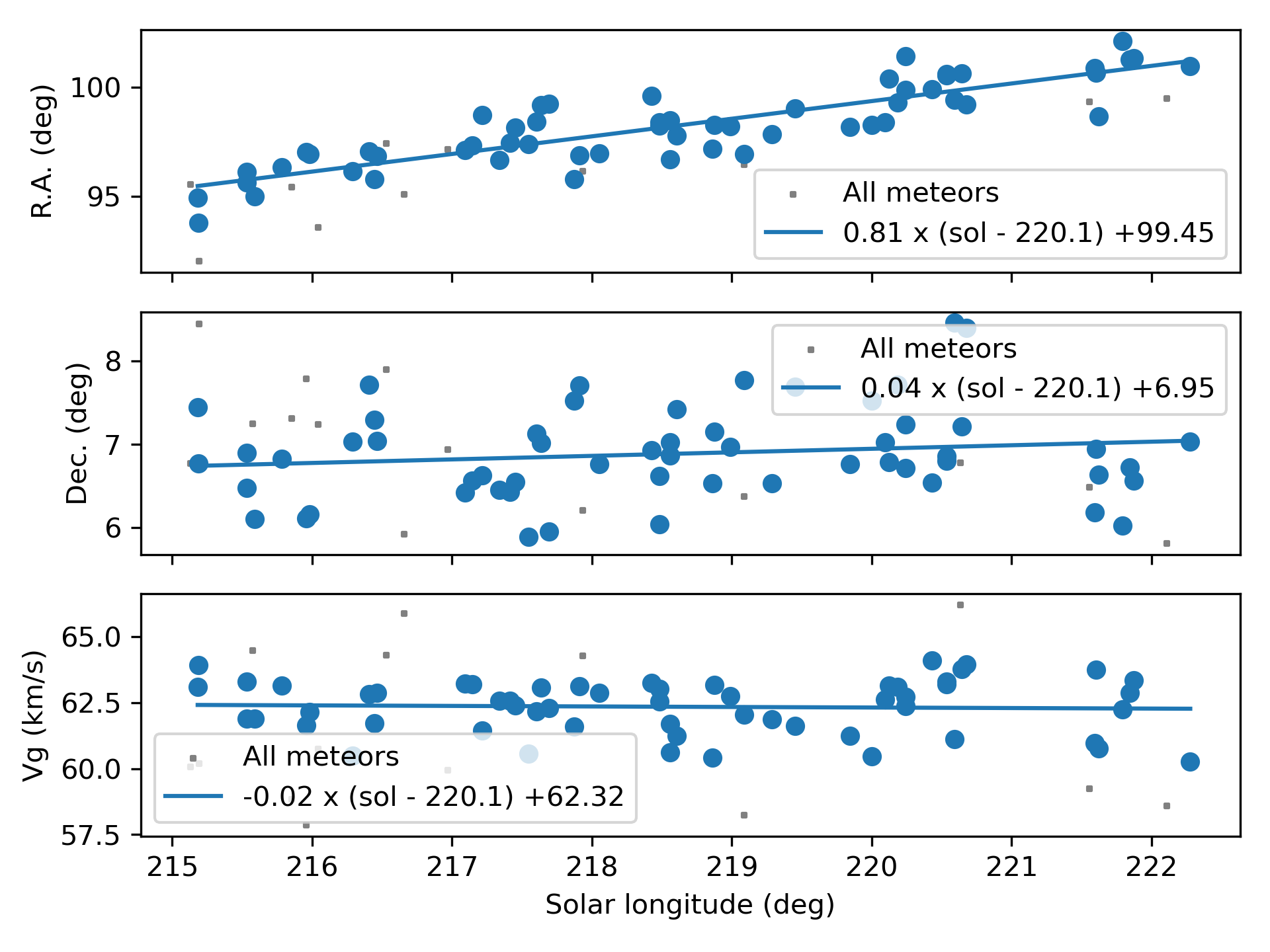

Figure 4 – The radiant drift.

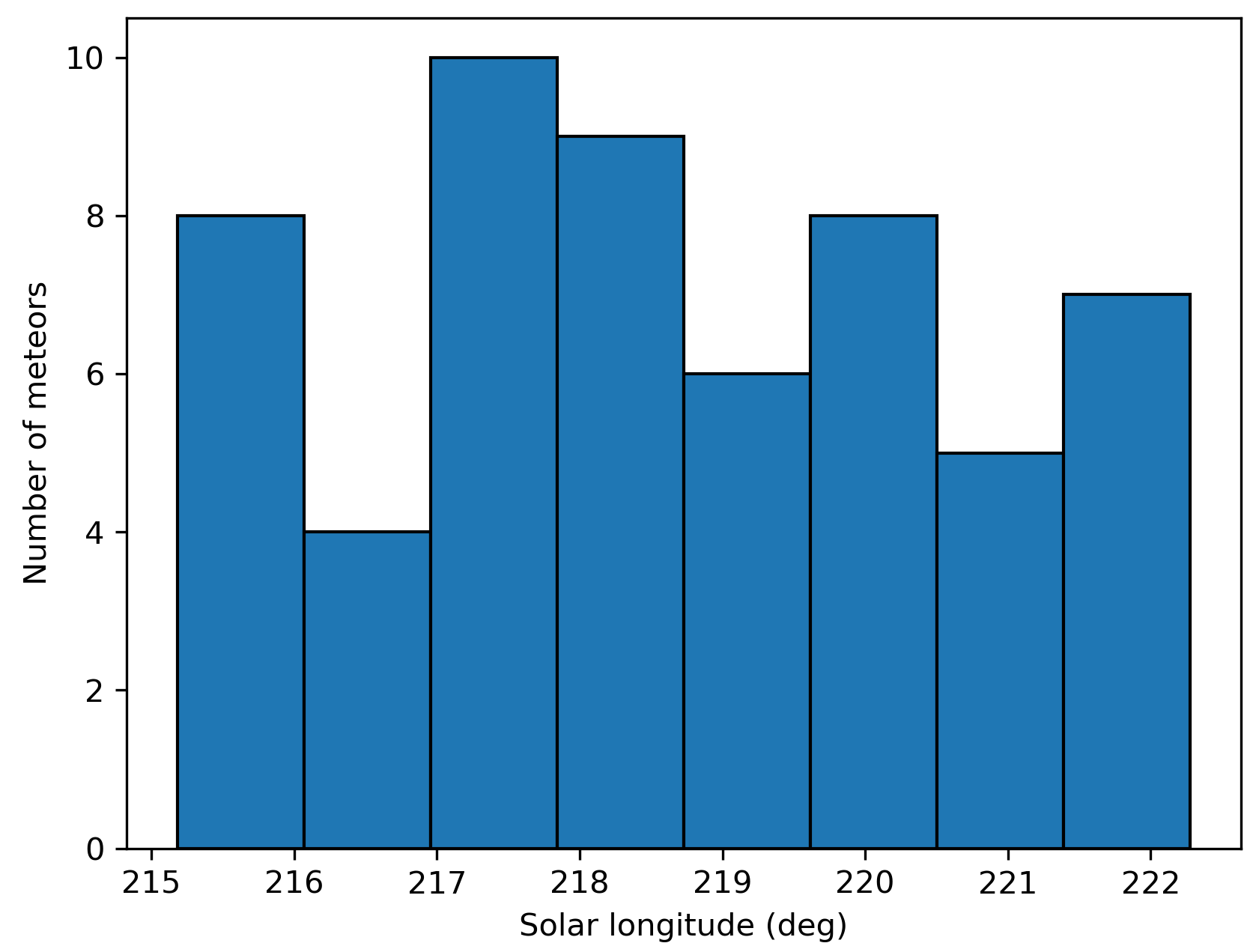

Figure 5 – The uncorrected number of shower meteors recorded per degree in solar longitude.

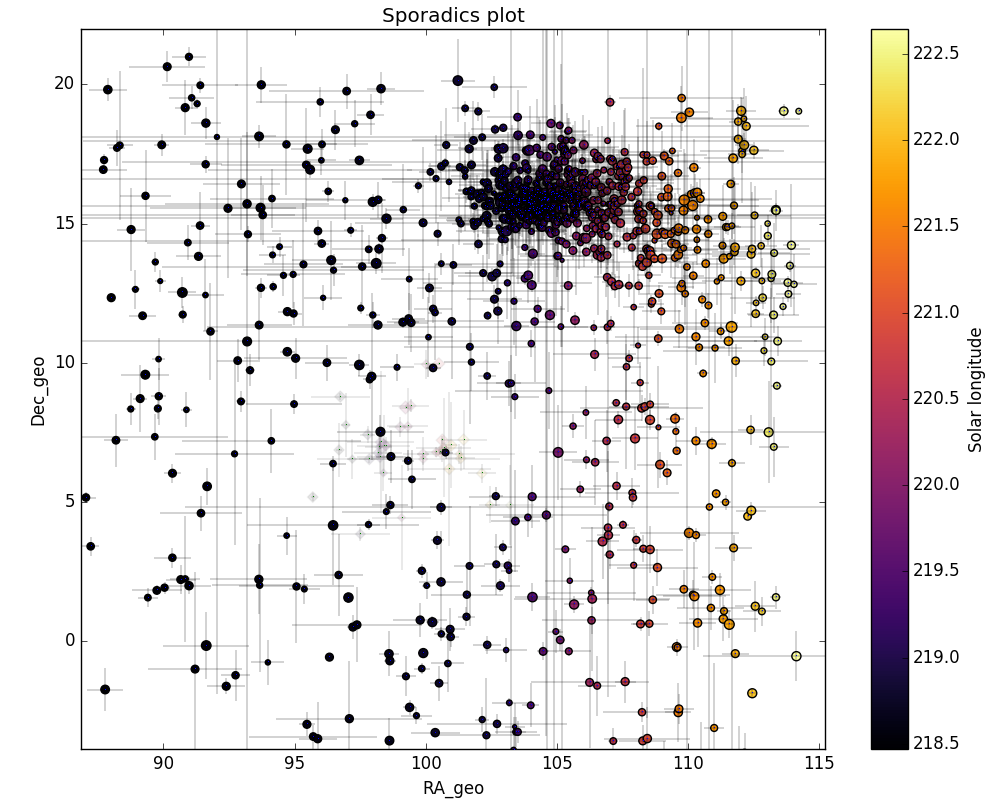

Figure 6 – All non-shower meteor radiants in geocentric equatorial coordinates during the shower activity. The pale diamonds represent the shower radiants plots, error bars represent two sigma values in both coordinates.

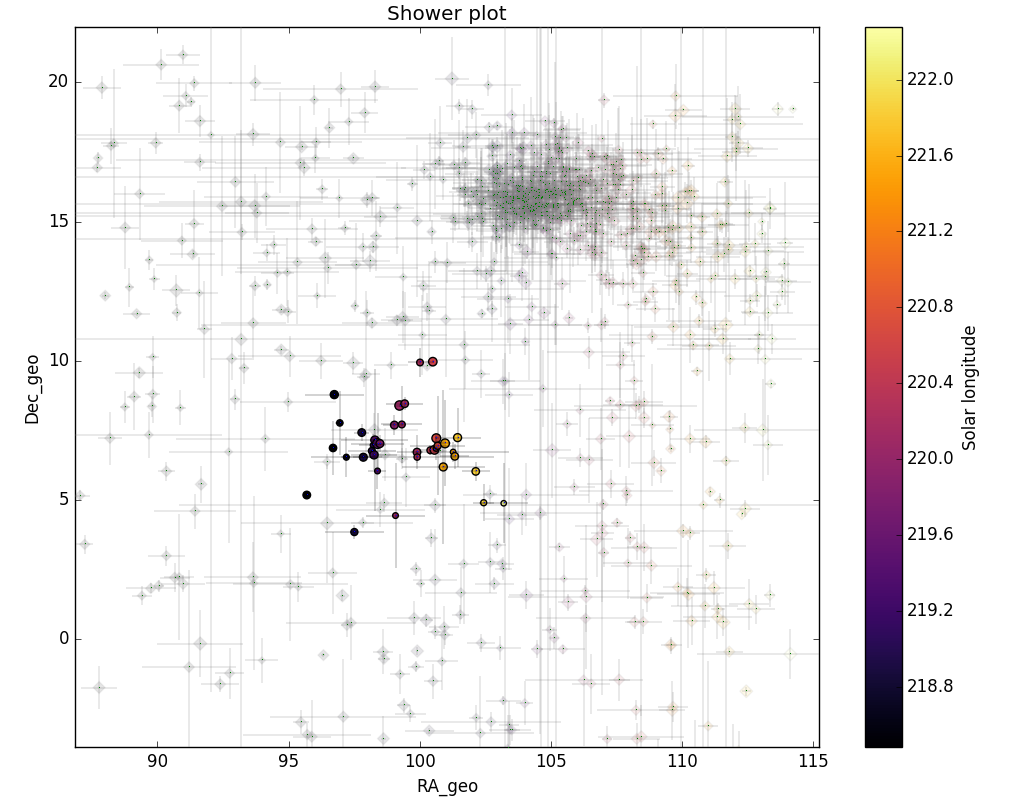

Figure 7 – The reverse of Figure 6, now the shower meteors are shown as circles and the non-shower meteors as grayed out diamonds.

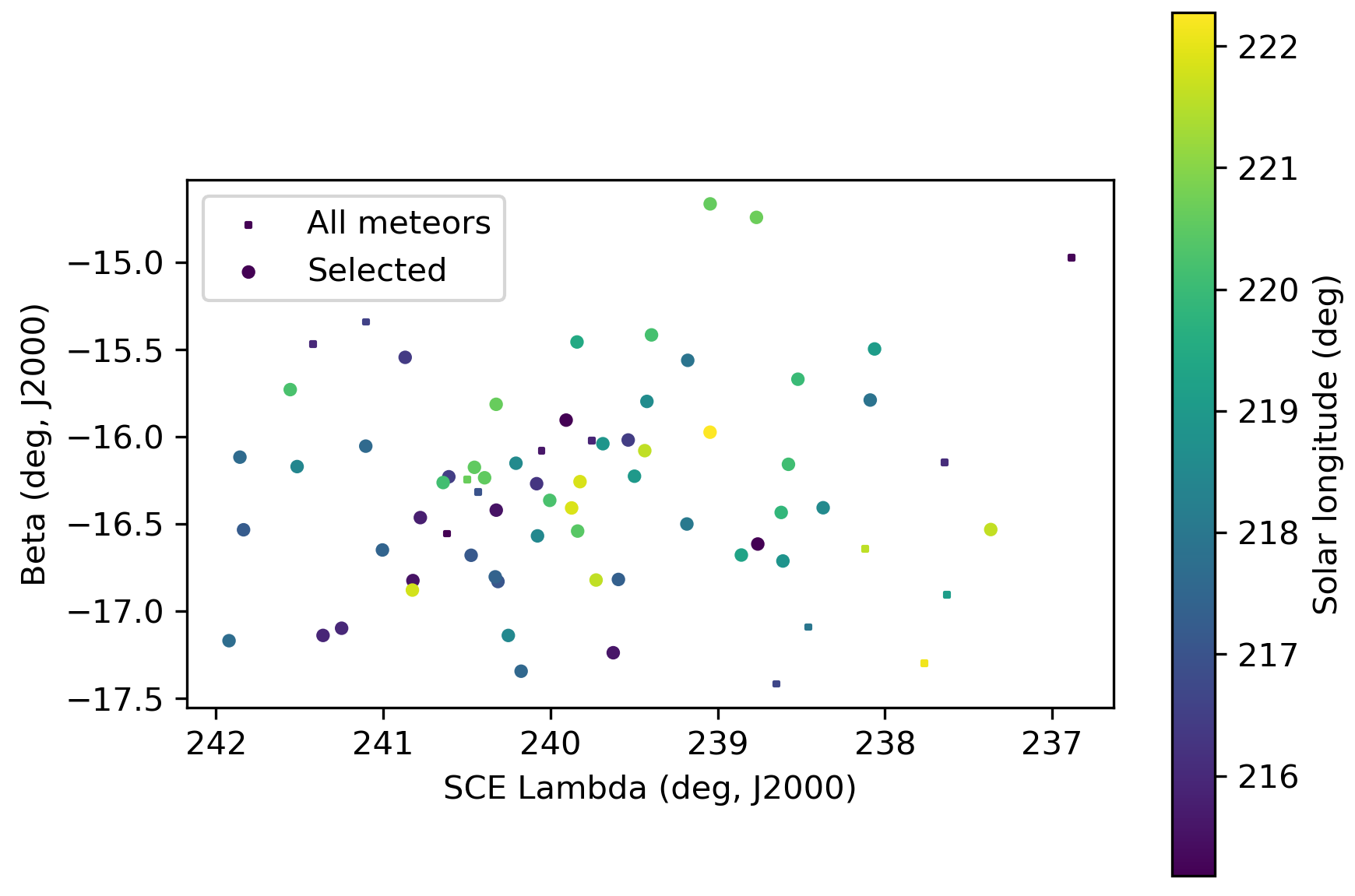

Figure 8 – The radiant distribution during the solar-longitude interval 215° – 222° in Sun centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates.

The shower had a median geocentric radiant with coordinates R.A. = 99.5°, Decl. = +7.0°, within a circle with a standard deviation of ±0.9° (equinox J2000.0). The radiant drift in R.A. is +0.81° on the sky per degree of solar longitude and +0.04° in Dec., both referenced to λʘ = 220.1° (Figures 3 and 4). The uncorrected raw numbers of shower meteors per degree in solar longitude show a fluctuating activity level (Figure 5) since poor weather clouded out many cameras during some days of the shower activity. Figures 6 and 7 show that the new activity source appeared on top of the sporadic background noise. The median Sun-centered ecliptic coordinates were λ – λʘ = 239.7°, β = –16.2° (Figure 8). The geocentric velocity was 62.3 ± 0.2 km/s. The shower parameters as obtained by the GMN method are listed in Table 1.

3 Shower classification based on orbits

Meteor shower identification strongly depends on the methodology used to select candidate shower members. The sporadic background is everywhere present and risks contamination of the selections of shower candidates. In order to double check GMN meteor shower detections, another method, based on orbit similarity criteria is used. This approach serves to make sure that no spurious radiant concentrations are mistaken as new meteor showers.

A reference orbit is required to start an iterative procedure to approach a mean orbit, which is the most representative orbit for the meteor shower as a whole, removing outliers and sporadic orbits (Roggemans et al., 2019). Three different discrimination criteria are combined in order to have only those orbits which fit the different criteria thresholds. The D-criteria that we use are these of Southworth and Hawkins (1963), Drummond (1981) and Jopek (1993) combined. Instead of using a cutoff value for the thresholds of the D-criteria, these values are considered in different classes with different thresholds of similarity. Depending on the dispersion and the type of orbits, the most appropriate threshold of similarity is selected to locate the best fitting mean orbit as the result of an iterative procedure.

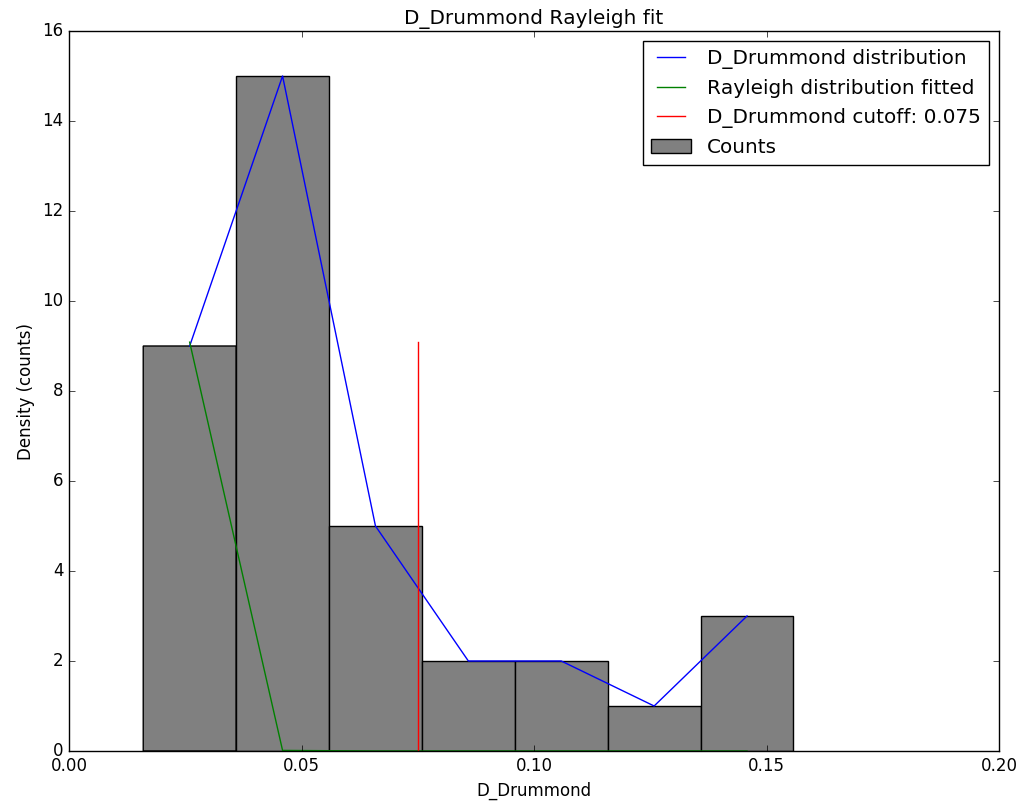

Figure 9 – Rayleigh distribution fit and Drummond DD criterion cutoff.

The D-criteria cutoff has not been derived by Rayleigh statistics but manually and set to DD < 0.075 (Figure 9). The use of D-criteria requires caution as the threshold values differ for different types of orbits. In this case, we distinguish seven classes of similarity:

- Poor: DSH < 0.2 & DD < 0.08 & DJ < 0.2.

- Very low: DSH < 0.15 & DD < 0.06 & DJ < 0.15.

- Low: DSH < 0.125 & DD < 0.05 & DJ < 0.125.

- Medium low: DSH < 0.1 & DD < 0.04 & DJ < 0.1.

- Medium high: DSH < 0.075 & DD < 0.03 & DJ < 0.075.

- High: DSH < 0.05 & DD < 0.02 & DJ < 0.05.

- Very high: DSH < 0.025 & DD < 0.01 & DJ < 0.025;

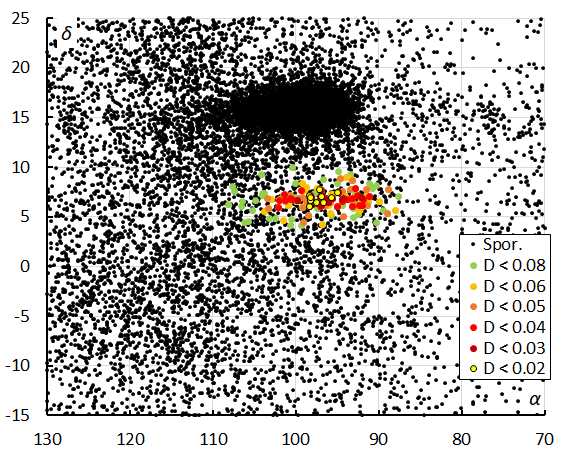

Figure 10 – The radiant distribution during the solar-longitude interval 208° – 229° in equatorial coordinates, color-coded for different threshold values of the DD orbit similarity criteria.

This method resulted in a mean orbit with 143 related orbits that fit within the similarity threshold with DSH < 0.2, DD < 0.08 and DJ < 0.2, recorded between October 21 and November 11, 2025. This activity period is significantly longer than what has been detected based on the radiant association method. The plot of the radiant positions in equatorial coordinates, color-coded for different D-criteria thresholds, has its radiant at 97.0° in Right Ascension and +6.8° in declination (Figure 10). The radiant positions appear as a long-stretched track caused by the radiant drift mainly in Right Ascension with Δα/Δλʘ = +0.89° and only Δδ/Δλʘ = –0.03° in declination. The dense radiant cloud 10° north of M2025-V1 are the annual major shower Orionids (ORI#8). Another less dense concentration around α = 115° and δ = –7° is caused by the November Hydrids (NHD#245), a shower that was removed from the MDC Working List because it was based on too few orbits (two). GMN observations proved that this shower exists but appears earlier in time than assumed in Jenniskens (2006). Around α = 77° and δ = +15° is another concentration which includes members of the alpha-Taurids (ATI#879) which were active between solar longitude 208° and 209°.

Figure 11 – The radiant distribution during the solar-longitude interval 208° – 229° in Sun-centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates, color-coded for different threshold values of the DD orbit similarity criteria.

The radiant appears very compact in the plot in Sun-centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates (Figure 11) with an almost neglectable radiant drift. Radiants that fit the orbit similarity class with DSH < 0.2 & DD < 0.08 & DJ < 0.2 are all outliers which may be an indication that these thresholds are too tolerant. To avoid contamination with sporadic orbits only orbits that fit within the thresholds DSH < 0.125 & DD < 0.05 & DJ < 0.125 are taken into account for the solutions mentioned in Table 1.

Figure 11 shows some other interesting radiant concentrations, apart from the dense cloud with Orionids (ORI#8) and nu-Eridanids (NUE#337). At λ–λʘ = 225° and β = –30°, we see the kappa-Orionids (KOR#833). At λ–λʘ = 242° and β = –22°, we see the November Hydrids (NHD#245). At λ–λʘ = 253° and β = +5°, we see the epsilon-Geminids (EGE#23) and at λ–λʘ = 256° and

β = –3°, we see the zeta-Cancrids (ZCN#243), another removed shower because it had no original reference. GMN obtained evidence for the existence of this minor shower.

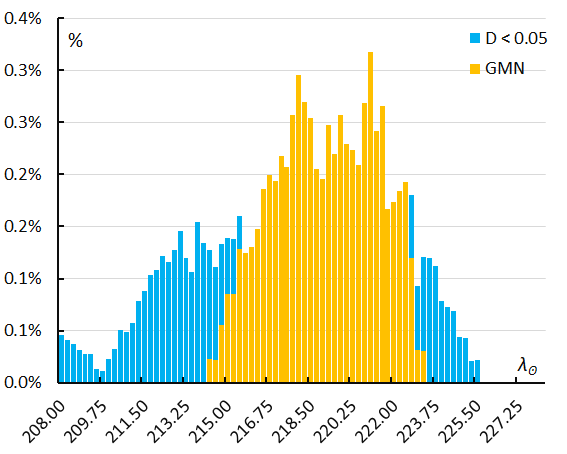

If we look at the ratio shower meteors to non-shower meteors recorded by GMN (Figure 12) in 2.0°-time bins in solar longitude in steps of 0.25°, we see that the orbit classification method identified M2025-V1 before λʘ = 214.0° and after λʘ = 223.0°, suggesting a longer activity period than what was covered by the radiant classification method. The fluctuations on the activity profile can be explained as due to small number statistics with 10 to 17 M2025-V1 meteors at best during each interval. Bad weather hampered many GMN cameras between λʘ = 221.0° – 227°.

Both methods identified 39 meteors in common. The radiant method associated 18 meteors not confirmed by the orbit identification method. The orbit shower identification had 32 meteors not found by the radiant association method, 30 of these recorded before or after the activity period obtained by the radiant association method.

Figure 12 – The percentage of shower meteors relative to the total number of meteors recorded by GMN. Orange is the result for the GMN shower classification, blue for the orbit D-criteria method.

4 Orbit and parent body

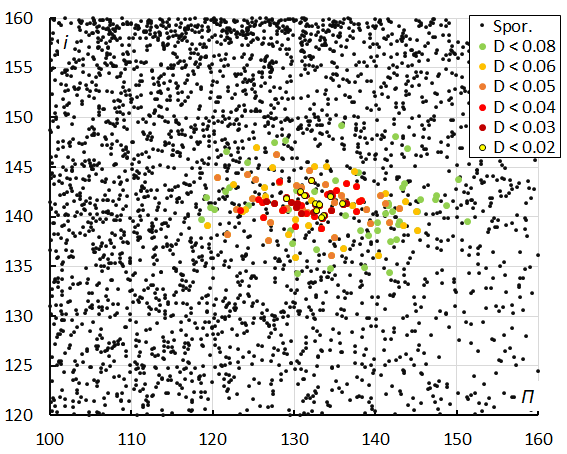

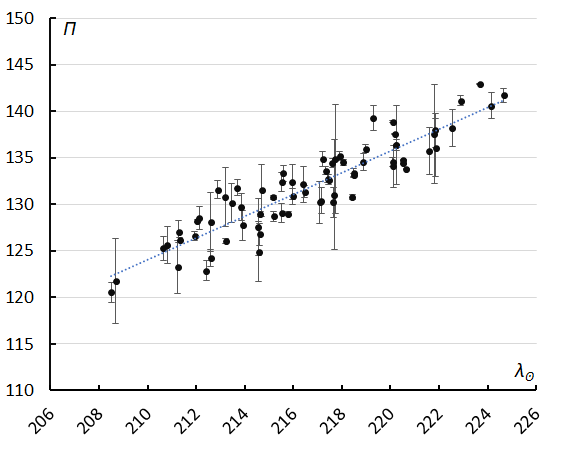

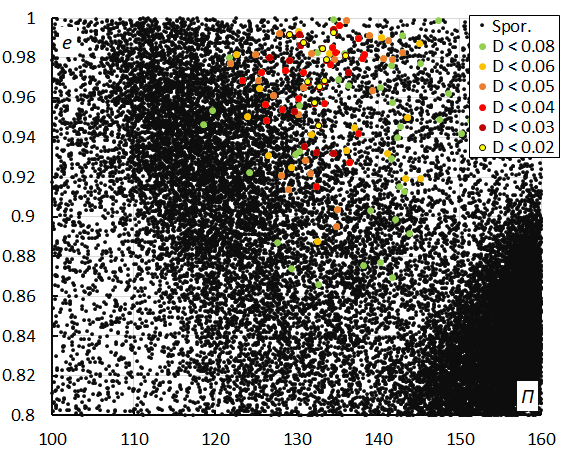

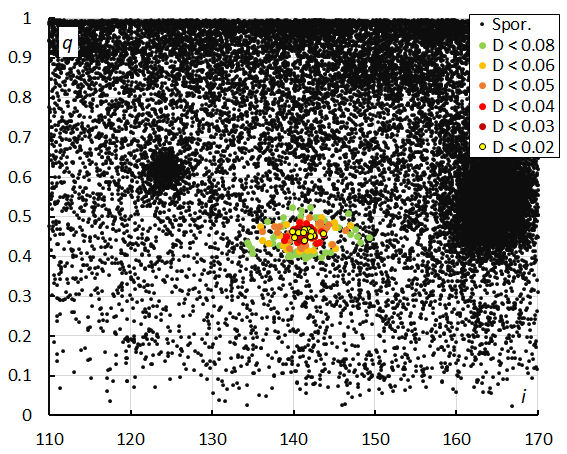

Looking at the diagram of inclination versus longitude of perihelion (Figure 13) there is a lot of scatter for the lower similarity classes which should be ignored. The dispersion in longitude of perihelion Π is due to the progression of the longitude of perihelion in function of time (expressed as solar longitude in Figure 14). The inclination remains stable around 141°. The progression of the longitude of perihelion combined with the uncertainties on the eccentricity with e = 0.970 ± 0.029 results in a lot of scatter in the diagram with Π versus e (Figure 15). The low similarity thresholds appear as outliers in this diagram too.

Figure 13 – The diagram of the inclination i versus the longitude of perihelion Π color-coded for different classes of D criteria thresholds, for λʘ between 208° and 229°.

Figure 14 – The evolution of the longitude of perihelion Π in function of the solar longitude λʘ.

Figure 15 – The diagram of the eccentricity e versus the longitude of perihelion Π color-coded for different classes of D criteria threshold, for λʘ between 208° and 229°.

Figure 16 – The diagram of the eccentricity e versus the inclination i color-coded for different classes of D criteria threshold, for λʘ between 208° and 229°.

The diagram of eccentricity versus inclination shows M2025-V1 dispersed in eccentricity but rather narrow in inclination. Two other such trails are visible at i = 130° which is the kappa-Ursae Majorids (KUM#445), and at i = 124°, which is the Leonis Minorids (LMI#22), both dispersed in eccentricity. All these meteor showers have a high geocentric velocity of 60+ km/s and the slightest velocity measurement uncertainty results in a large dispersion in eccentricity which is very sensitive to error margins on velocity.

The M2025-V1 orbits appear very concentrated in perihelion distance q (Figure 17). The large concentration at right are the Orionids (ORI#8) and concentration at left are the Leonis Minorids (LMI#22).

Figure 17 – The diagram of the perihelion distance q versus the inclination i color-coded for different classes of D criteria threshold, for λʘ between 208° and 229°.

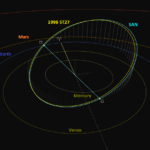

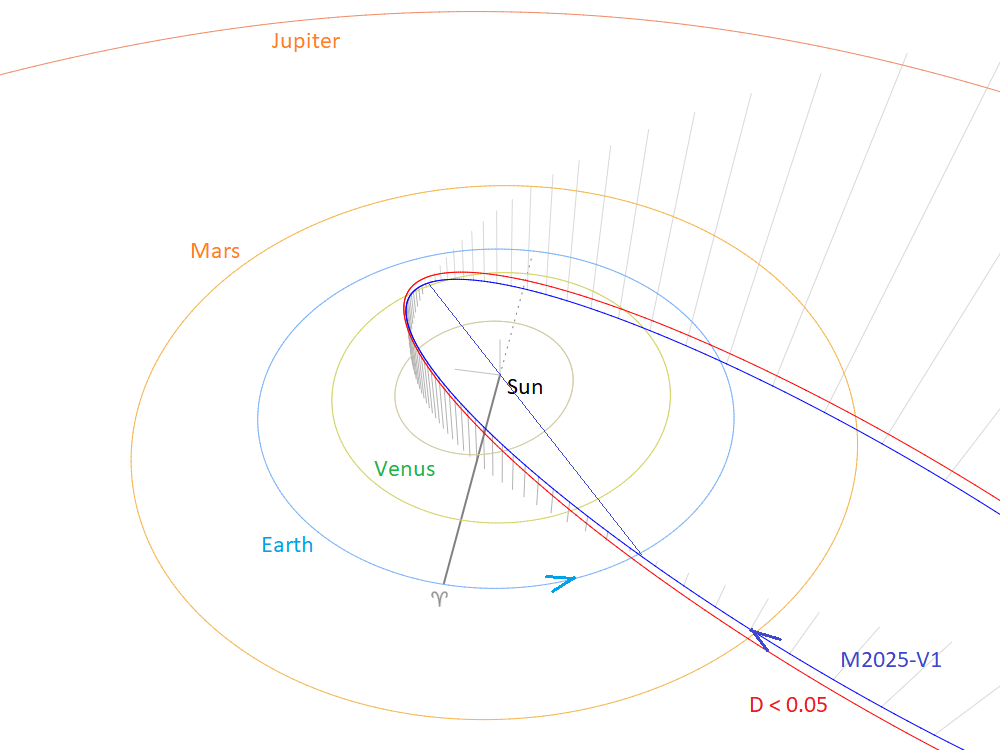

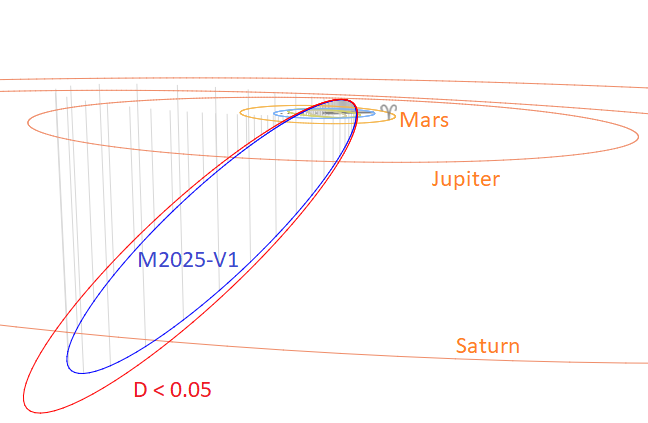

Figure 18 – Comparing the mean orbits for two solutions obtained by two methods, close-up at the inner Solar System. (Plotted with the Orbit visualization app provided by Pető Zsolt).

The Tisserand’s parameter relative to Jupiter, Tj (= –0.16) identifies the orbit as of a Long-Period Comet type orbit. Figure 18 compares two solutions as listed in Table 1 obtained by two different methods. The meteoroid stream encounters the Earth from south of the ecliptic at its ascending node. Figure 19 shows the orbits of the two solutions as viewed from another perspective. The orbit shower association method selected M2025-V1 meteors almost a week sooner than the radiant association method, with a slightly higher geocentric velocity that results in a higher eccentricity and larger semi-major axis.

Figure 19 – Comparing the mean orbits for two solutions obtained by two methods. (Plotted with the Orbit visualization app provided by Pető Zsolt).

Table 1 – Comparing solutions derived by two different methods, GMN-method based on radiant positions and orbit association for DD < 0.05 and DD < 0.04.

| GMN | DD < 0.05 | DD < 0.04 | |

| λʘ (°) | 220.1 | 217.1 | 216.5 |

| λʘb (°) | 215.0 | 208.4 | 210.8 |

| λʘe (°) | 222.3 | 224.7 | 222.5 |

| αg (°) | 99.5 | 97.0 | 96.9 |

| δg (°) | +7.0 | +6.8 | +6.8 |

| Δαg (°) | +0.81 | +0.90 | +0.94 |

| Δδg (°) | +0.04 | –0.03 | +0.00 |

| vg (km/s) | 62.3 | 62.8 | 62.8 |

| Hb (km) | 109.8 | 109.9 | 110.4 |

| He (km) | 95.8 | 95.1 | 95.4 |

| Hp (km) | 100.9 | 99.9 | 100.6 |

| MagAp | –0.8 | –1.0 | –1.0 |

| λg (°) | 99.77 | 97.2 | 97.2 |

| λg – λʘ (°) | 239.37 | 240.3 | 240.3 |

| βg (°) | –16.16 | –16.5 | –16.5 |

| a (A.U.) | 10.855 | 15.2 | 15.5 |

| q (A.U.) | 0.442 | 0.459 | 0.458 |

| e | 0.959 | 0.970 | 0.971 |

| i (°) | 141.2 | 141.4 | 141.4 |

| ω (°) | 97.5 | 95.1 | 95.3 |

| Ω (°) | 38.6 | 36.6 | 36.5 |

| Π (°) | 136.1 | 131.7 | 131.8 |

| Tj | –0.16 | –0.31 | –0.32 |

| N | 57 | 71 | 43 |

A top 10 parent-body search resulted in no candidates with a threshold for the Drummond DD criterion value low enough to be a possible parent (Table 2). Orbit integrations are required to reconstruct the dynamical evolution to identify the parent body, if this has been discovered. M2025-V1 could be for instance an old dust trail somehow related to comet 1P/Halley which has been associated with several other meteor showers that were identified as components of the “Orionid Tail”.

Table 2 – Top ten matches of a search for possible parent bodies with DD < 0.3.

| Name | DD |

| C/1868 L1 (Winnecke) | 0.186 |

| 1P/Halley | 0.219 |

| C/2000 W1 (Utsunomiya-Jones) | 0.261 |

| C/1845 L1 (Great June comet) | 0.262 |

| C/1914 J1 (Zlatinsky) | 0.271 |

| C/1902 R1 (Perrine) | 0.279 |

| C/1743 Q1 | 0.281 |

| C/1596 N1 | 0.283 |

| C/1808 M1 (Pons) | 0.287 |

| C/2025 A6 (Lemmon) | 0.288 |

5 Past years’ activity

Checking past GMN data on orbits that fit within the D-criteria threshold DSH < 0.125 & DD < 0.05 & DJ < 0.125, we found 45 orbits in 2024, 39 in 2023, 24 in 2022, 20 in 2021, 4 in 2020 and 3 in 2019. All orbits were recorded between 210° and 228° in λʘ, most of them between 217° and 225°. Among the 529076 SonotaCo orbits registered between 2007 and 2024, 47 orbits were found during these years. EDMOND had 33 orbits in its dataset recorded between 2009 and 2022. CAMS had 22 orbits of this shower recorded between 2010 and 2016. The shower has definitely an annual activity.

In personal communication Peter Jenniskens pointed attention that this shower had been identified late in the writing of his book (Jenniskens, 2023) and has been listed as the October epsilon-Monocerotids, although not yet reported or listed in the IAU-MDC Working List of Meteor Showers (Jenniskens, 2026).

A review of past visual observations reveals visually derived radiants in the target region during late October and early November.

The earliest potential sighting of M2025-V1 appears to by Colonel G.L Tupman on 7 November 1869 (Gruber, 1879) who recorded a radiant position of R.A. 103° and Decl. +07° Tupman described this as “an active and well-defined shower”. Doctor L. Gruber then combined his personal 1877 observations with Tupman’s to determine a shower profile for the probable M2025-V1. He describes the shower as active from 2–14 November with a maximum on 10 November. The radiant position is given as R.A. 103° and Decl. +03°.

William Denning (1899) surprisingly does not seem to have seen M2025-V1 except for potentially in 1877 when he records a radiant at R.A. 107° and Decl. +11° with activity ranging from 10–13 November.

Cuno Hoffmeister (1948) recorded three possible radiants for M2025-V1 from 1935-37 as follows:

- Number 2539 (1935) λʘ= 218.6°, R.A. 096° and Decl. +05°.

- Number 4394 (1937) λʘ= 217.2°, R.A. 103° and Decl. +11°.

- Number 4409 (1937) λʘ= 219.2°, R.A. 100° and Decl. +10°.

In more recent times M2025-V1 has potentially been recorded by Darryl Skelsey in NSW on 2 November 1972 (Buhagiar, 1982). Skelsey’s radiant position was given as R.A. 102° and Decl. +06° In Western Australia, Maurice Clark and Michael Buhagiar (Buhagiar, 1982) appear to have recorded M2025-V1 on six occasions during the 1970’s. Buhagiar described his shower as active between 24 October and 11 November with a maximum ZHR of 2 on 5 November. The mean radiant position was R.A. 105° and Decl. +06°.

During the period 1977–2002, WAMS/NAPOMS observers appear to have recorded M2025-V1. Potential activity was detected over the period 25 October to 8 November. Rates were generally low and varied from year to year. A broad maximum seems to occur between 31 October and 3 November. Six radiants were derived from meteor plots using gnomic projection maps. The mean position of these radiants was R.A. 101° and Decl. +09°.

6 Conclusions

A prominent source of meteor activity has been observed by the Global Meteor Network with a radiant in the constellation of Monoceros, first noted by Jenniskens (2023). The shower association method based on the orbit similarity criteria indicated a longer activity period starting at least five days earlier and lasting two days longer than found by the radiant association method. A search through past meteor orbit datasets revealed that this meteor shower produces a very weak but annual activity since meteor camera network data are available.

Acknowledgments

This report is based on the data of the Global Meteor Network (Vida et al., 2020a; 2020b; 2021) which is released under the CC BY 4.0 license. We thank all 825 participants in the Global Meteor Network project for their contribution and perseverance. A list with the names of the volunteers who contribute to GMN has been published in the 2024 annual report (Roggemans et al., 2025).

The following 214 cameras recorded one or more meteors that were identified as members of this new meteor shower:

AU0002, AU000B, AU000C, AU000D, AU000R, AU000S, AU000U, AU001A, AU001B, AU001E, AU001Q, AU001S, AU001Y, AU001Z, AU0030, AU003E, AU003H, AU003H_2, AU0042, AU0043, BA0003, BE0002, BE0006, BE0008, BE000A, BE000G, BE000L, BE000P, BE000R, BE000U, BE000W, BE0016, BE0017, BE0018, BE001A, BG0003, BG000C, CA000R, CA001J, CA002N, CA0035, CZ0002, CZ0006, CZ000C, CZ000J, CZ000L, CZ000Q, CZ000R, CZ000U, CZ000X, DE0001, DE0004, DE000B, DE000C, DE000X, DE0011, DK0001, DK000C, FR0006, FR000A, FR000R, FR000X, FR000Z, GR0002, GR0003, HR0007, HR0025, HR0027, HR002G, HR002H, HR002J, HR002V, HR002W, HR002X, HU0002, HU0004, HU0005, HU000A, HU000B, HU000C, KR000B, KR000F, KR000J, KR000K, KR000P, KR000R, KR000S, KR001D, KR0023, KR002E, KR002J, KR002S, KR0036, KR003N, KR003T, KR003U, KR003W, NL0001, NL0006, NL0009, NL000C, NL000D, NL000K, NL000M, NL000R, NL000W, NL0010, NL0013, NL0014, NL0019, NZ0004, NZ000H, NZ0016, NZ001A, NZ001G, NZ0021, NZ0026, NZ0027, NZ002C, NZ002D, NZ002J, NZ002R, NZ002U, NZ002V, NZ002X, NZ002Y, NZ0030, NZ0037, NZ003B, NZ003E, NZ003Q, NZ003T, NZ003W, NZ004U, NZ004Z, NZ005G, NZ0063, PL0008, PL000F, PL000G, RO0001, RU000E, RU0017, SI0002, SI0004, SK0005, UA0003, UA0006, UK0008, UK001L, UK001S, UK001Z, UK003V, UK004E, UK004F, UK004J, UK005Y, UK006J, UK006V, UK0078, UK0079, UK007J, UK0080, UK008A, UK008F, UK009K, UK009Q, UK00A0, UK00AQ, UK00B0, UK00CD, UK00CS, UK00DE, US0005, US000D, US000G, US000J, US000R, US000U, US000V, US001R, US0020, US002A, US002Y, US003Q, US003T, US0044, US004C, US004P, US0055, US005A, US005D, US005E, US005G, US005J, US005Q, US005X, US005Y, USL00G, USL00K, USL00M, USL00P, USL00Q, USL016, USL017, USL018, USL019, USL01A, USL01B, USL01D, USL01E, USN001, USN002, USN003.

References

Buhagiar M. (1982). “Australian Visual Meteor Observations 1969-1982”. A private unpublished paper.

Denning W.F. (1899). “General Catalogue of Radiant Points and Meteoric Showers and of Fireballs and of Shooting Stars observed at more than one station”. Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society, 53, 203–292.

Drummond J. D. (1981). “A test of comet and meteor shower associations”. Icarus, 45, 545–553.

Gruber L. (1879). “Grubers set of radiant points for November 1–18”. British Association for the Advancement of Science, 49, 122.

Hoffmeister C. (1948). “Meteorstrome”. Leipzig, J.A. Barth.

Jenniskens P. (2006). Meteor Showers and their Parent Comets. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Jenniskens P. (2023). Atlas of Earth’s Meteor Showers, Amsterdam: Elsevier, page 481.

Jenniskens P. (2026). “Provisional meteor shower names (2022–2025)”. eMetN Meteor Journal, 11, xx–xx.

Jopek T. J. (1993). “Remarks on the meteor orbital similarity D-criterion”. Icarus, 106, 603–607.

Jopek T. J., Rudawska R. and Pretka-Ziomek H. (2006). “Calculation of the mean orbit of a meteoroid stream”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 371, 1367–1372.

Moorhead A. V., Clements T. D., Vida D. (2020). “Realistic gravitational focusing of meteoroid streams”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 494, 2982–2994.

Roggemans P., Johannink C. and Campbell-Burns P. (2019a). “October Ursae Majorids (OCU#333)”. eMetN Meteor Journal, 4, 55–64.

Roggemans P., Campbell-Burns P., Kalina M., McIntyre M., Scott J. M., Šegon D., Vida D. (2025). “Global Meteor Network report 2024”. eMetN Meteor Journal, 10, 67–101.

Southworth R. B. and Hawkins G. S. (1963). “Statistics of meteor streams”. Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics, 7, 261–285.

Vida D., Gural P., Brown P., Campbell-Brown M., Wiegert P. (2020a). “Estimating trajectories of meteors: an observational Monte Carlo approach – I. Theory”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 491, 2688–2705.

Vida D., Gural P., Brown P., Campbell-Brown M., Wiegert P. (2020b). “Estimating trajectories of meteors: an observational Monte Carlo approach – II. Results”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 491, 3996–4011.

Vida D., Šegon D., Gural P. S., Brown P. G., McIntyre M. J. M., Dijkema T. J., Pavletić L., Kukić P., Mazur M. J., Eschman P., Roggemans P., Merlak A., Zubrović D. (2021). “The Global Meteor Network – Methodology and first results”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 506, 5046–5074.