By Paul Roggemans, Denis Vida, Damir Šegon, James M. Scott, Jeff Wood

Abstract: Enhanced activity has been recorded during October 14 – 15, 2025 from the October epsilon-Carinids (OEC#1172) by the Global Meteor Network. 201 meteors belonging to this meteor shower were observed between 197.0° < λʘ < 204.0° during the period 2023 to 2025 from a radiant at R.A. = 110.7° and Decl.= –60.4°, with a geocentric velocity of 28.9 km/s. This case study confirms the existence of this meteor shower, and the most likely parent body is Asteroid 2010 HY22.

1 Introduction

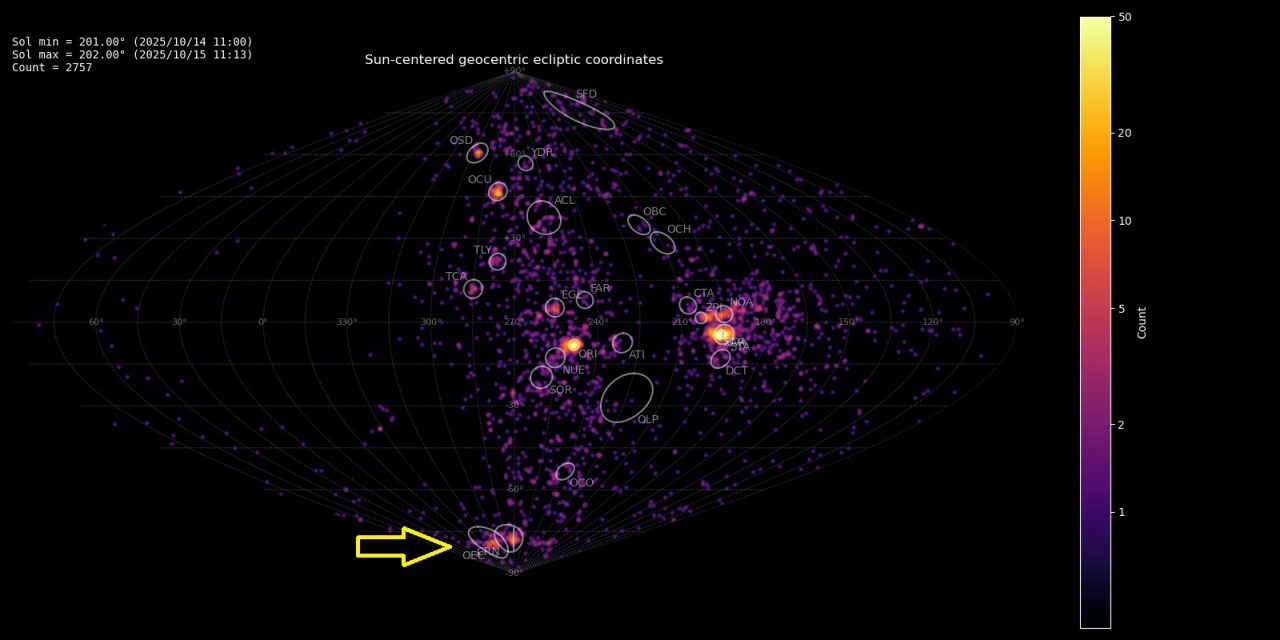

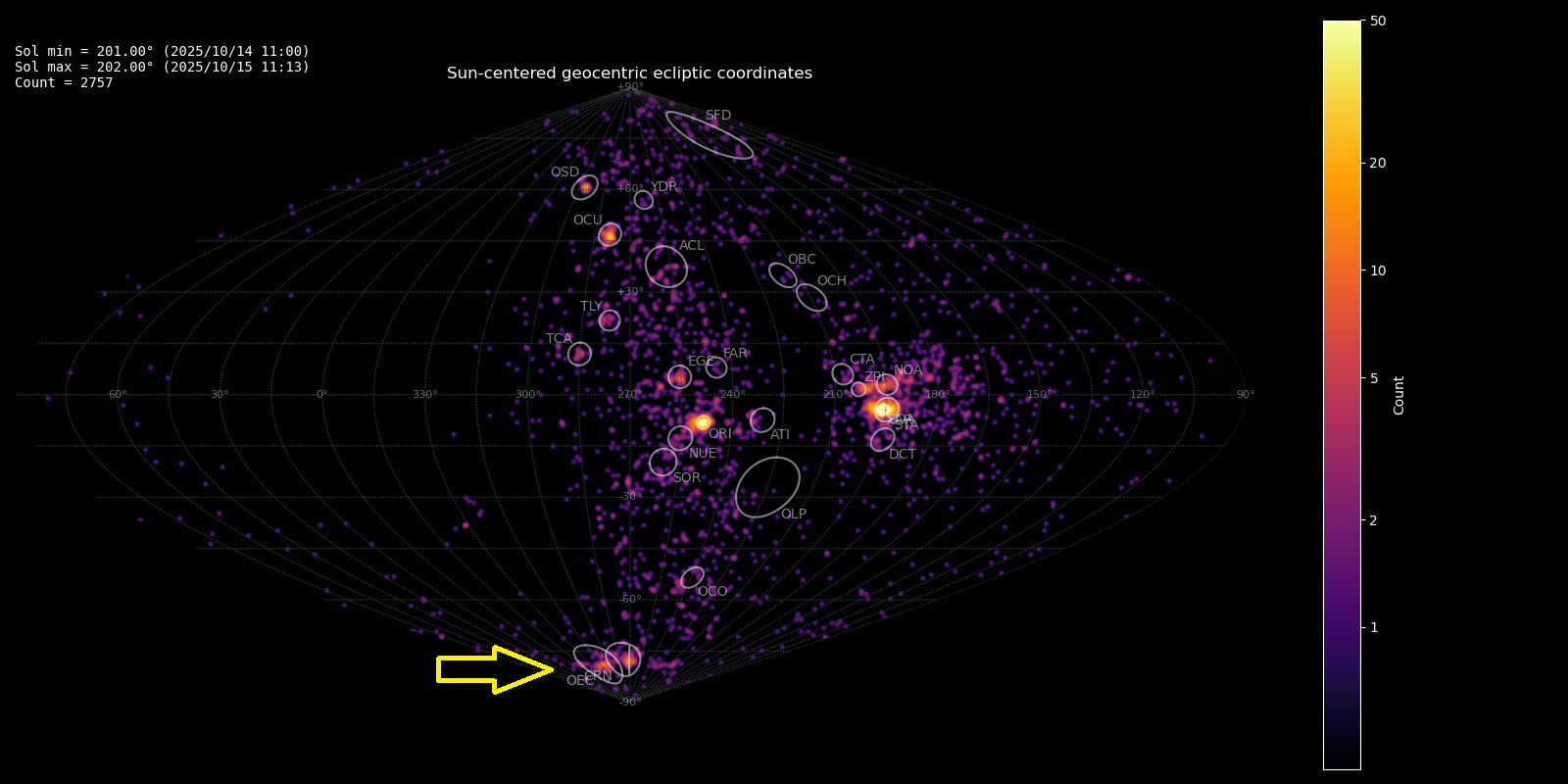

On 15 October 2025 some unusually strong activity was spotted near the South Pole (Figure 1). The radiant source was identified as the October epsilon-Carinids (OEC#1172), first reported in 2022 by Jenniskens (2023) from CAMS southern hemisphere low-light video observations in 2019–2021 with a total of 84 meteors identified as OEC#1172.

In 2025, Global Meteor Network detected 118 meteors identified as October epsilon-Carinids. Another 43 shower members were found in 2024 and 40 in 2023. The shower’s enhanced activity in 2025 and the significant statistical sample with 201 October epsilon-Carinids recorded in 2023–2025 justified a case study to improve the IAU-MDC working list of meteor showers for this poorly known activity source.

Figure 1 – Radiant density map with 2757 radiants obtained by the Global Meteor Network during 14–15 October, 2025. The position of the October epsilon-Carinids in Sun-centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates is marked with a yellow arrow.

2 Shower classification based on radiants

The GMN shower association criteria assume that meteors within 1° in solar longitude, within 5.1° in radiant in this case, and within 10% in geocentric velocity of a shower reference location are members of that shower. Further details about the shower association are explained in Moorhead et al. (2020). Using these meteor shower selection criteria, 201 orbits have been identified as October epsilon-Carinids.

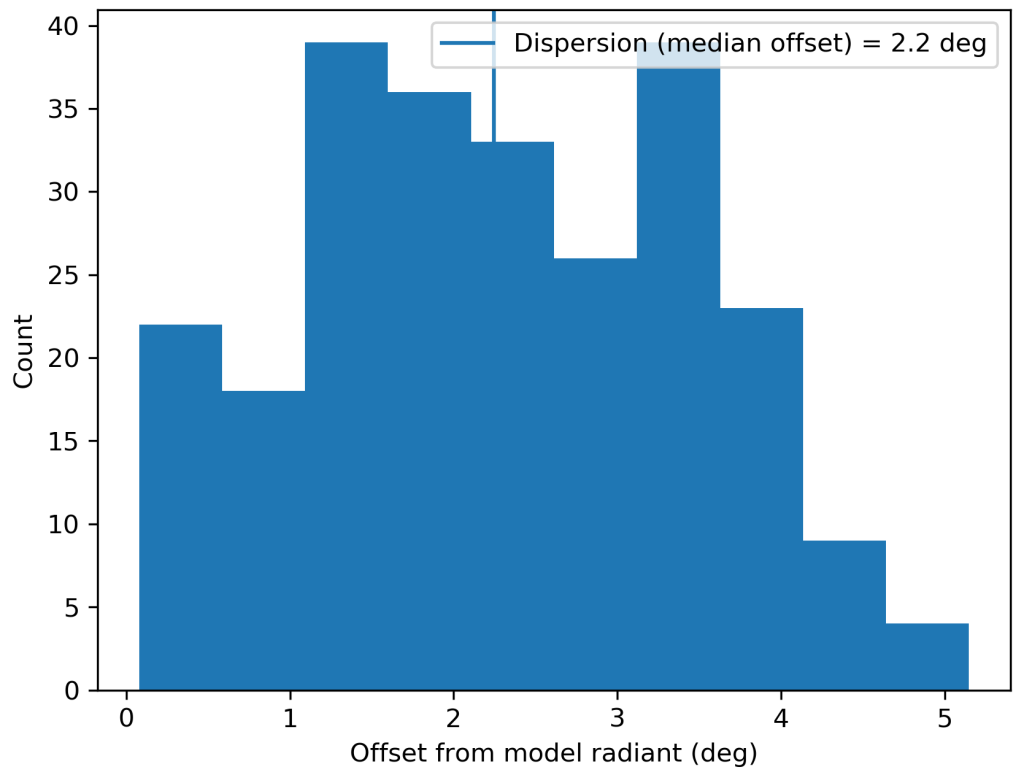

Figure 2 – Dispersion median offset on the radiant position.

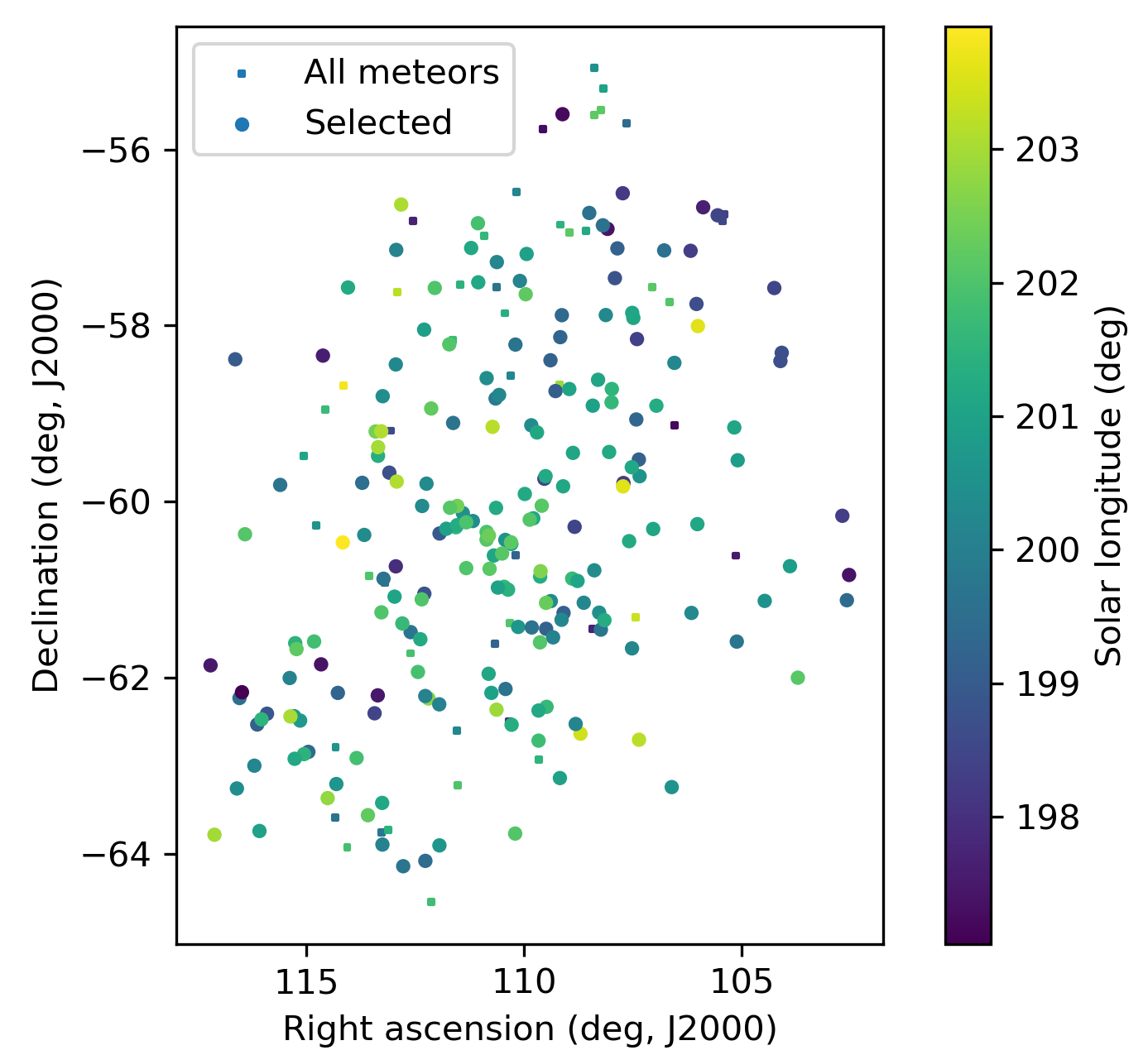

Figure 3 – The radiant distribution during the solar-longitude interval 197° – 204° in equatorial coordinates.

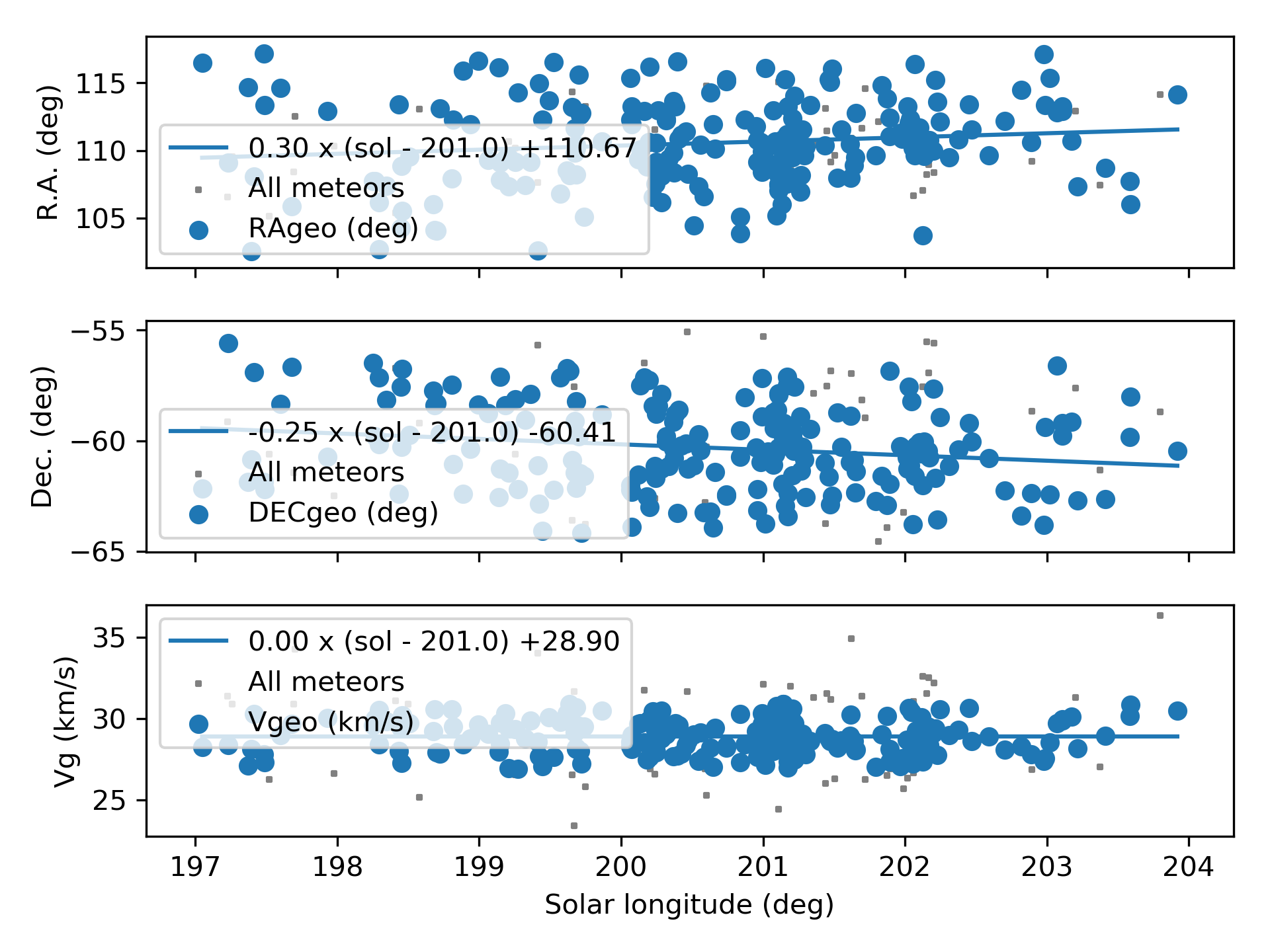

Figure 4 – The radiant drift.

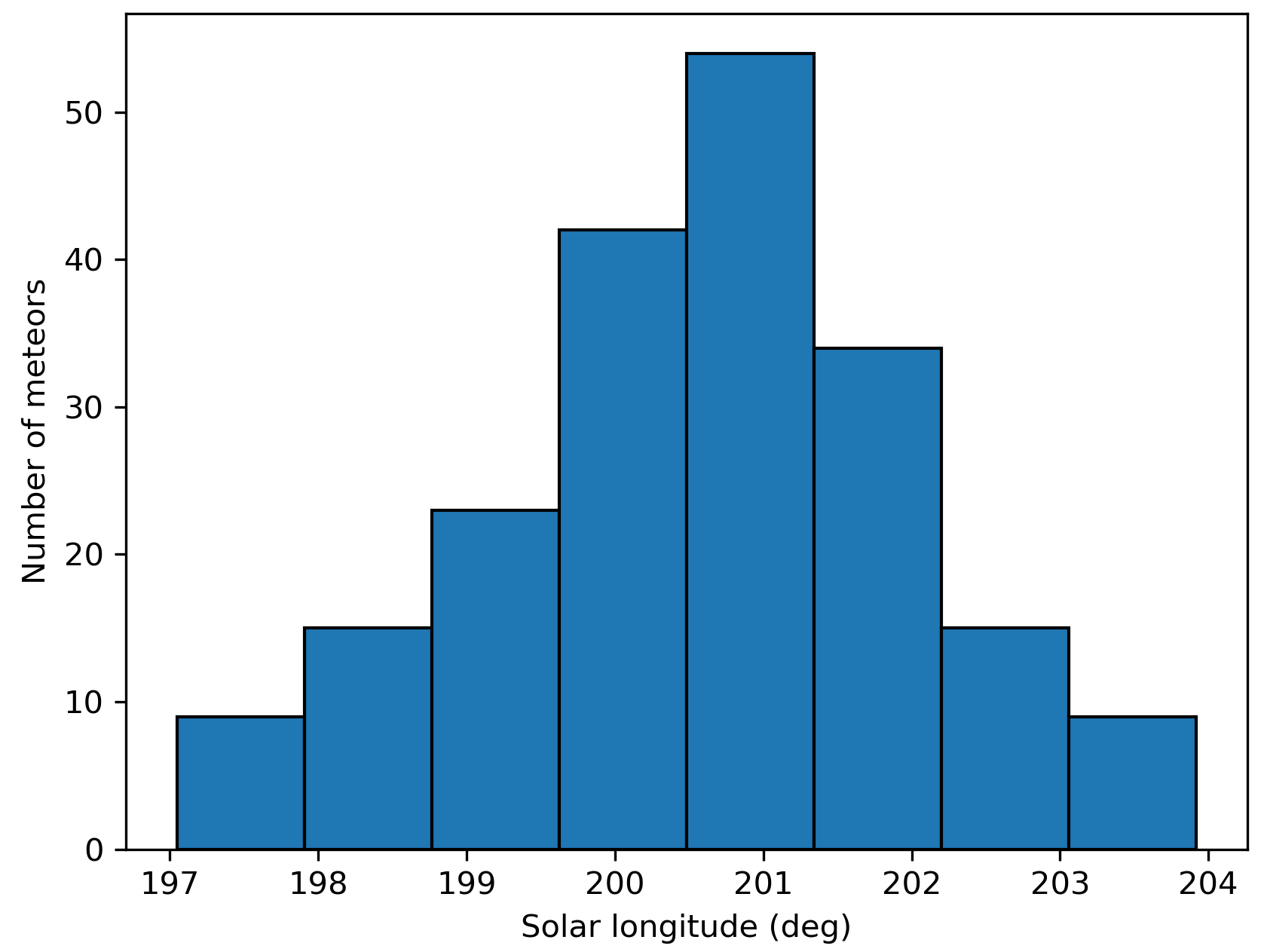

Figure 5 – The uncorrected number of shower meteors recorded per degree in solar longitude.

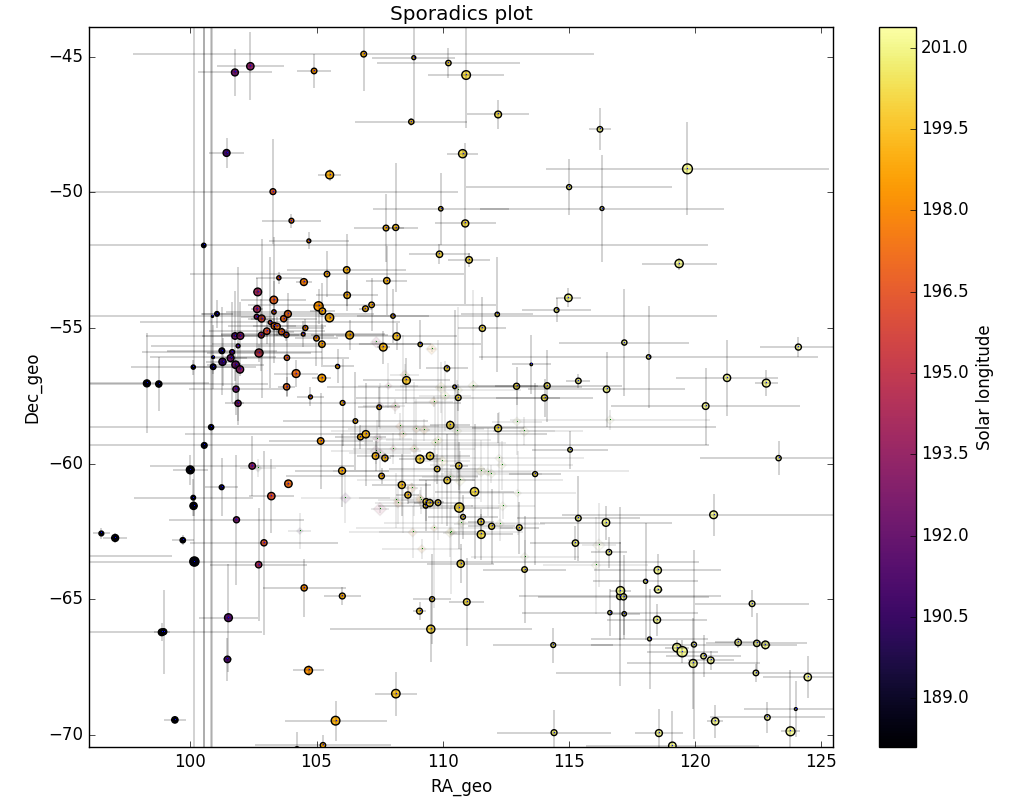

Figure 6 – All non-shower meteor radiants in geocentric equatorial coordinates during the shower activity. The pale diamonds represent the shower radiants plots, error bars represent two sigma values in both coordinates.

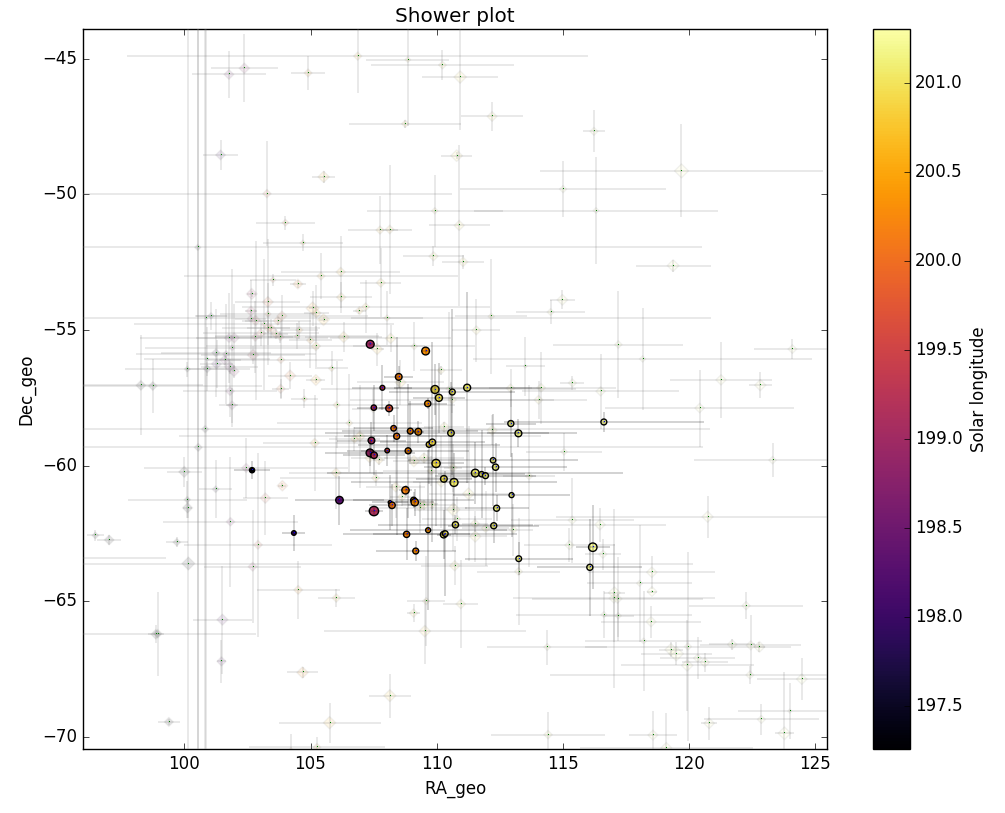

Figure 7 – The reverse of Figure 6, now the shower meteors are shown as circles and the non shower meteors as grayed out diamonds.

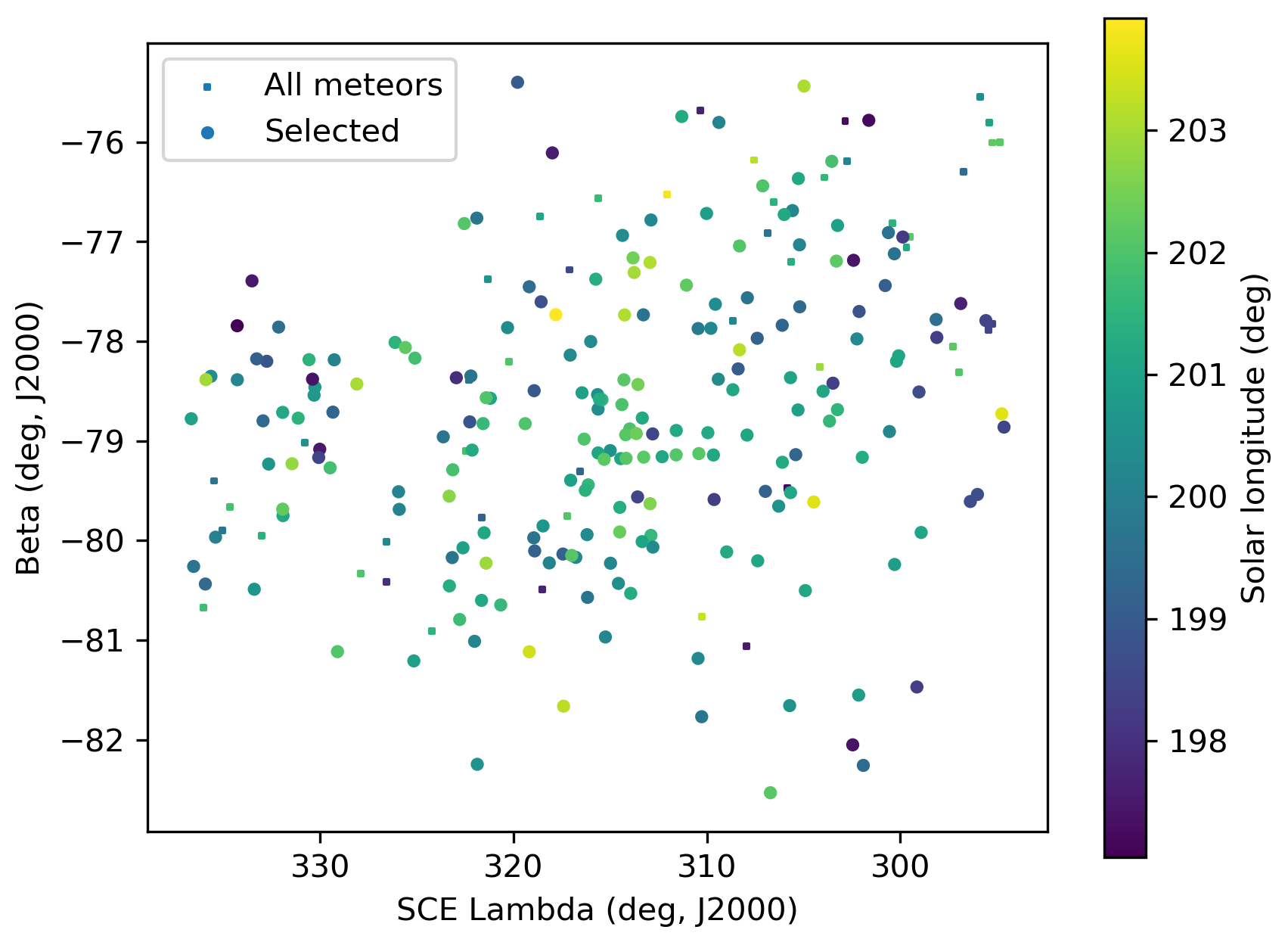

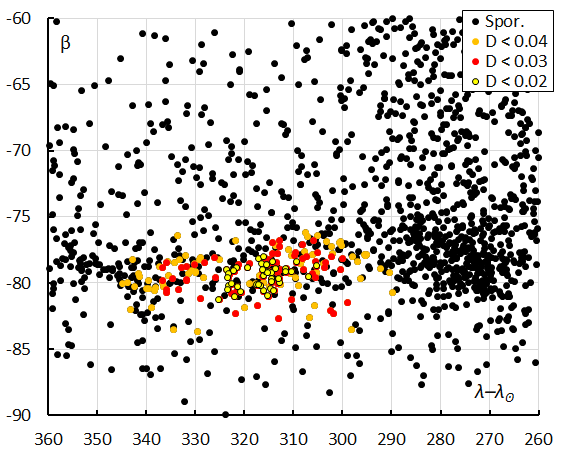

The shower was independently observed by 212 cameras in five countries (Australia, Brazil, Malaysia, New Zealand and South Africa). The shower had a median geocentric radiant with coordinates R.A. = 110.7°, Decl. = –60.4°, within a circle with a standard deviation of ±2.2° (equinox J2000.0). The radiant drift in R.A. is +0.30° on the sky per degree of solar longitude and –0.25° in Dec., both referenced to λʘ = 201.0° (Figures 3 and 4). The plot with uncorrected raw numbers of shower meteors per degree in solar longitude indicates that most OEC-meteors were recorded around λʘ = 201.0° (Figure 5). Figures 6 and 7 show that the October epsilon-Carinids appeared on top of the sporadic background noise. The median Sun-centered ecliptic coordinates were λ – λʘ = 315.1°, β = –78.9° (Figure 8). The geocentric velocity was 28.9 ± 0.1 km/s. The shower parameters as obtained by the GMN method are listed in Table 1.

Figure 8 – The radiant distribution during the solar-longitude interval 197° – 204° in Sun centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates.

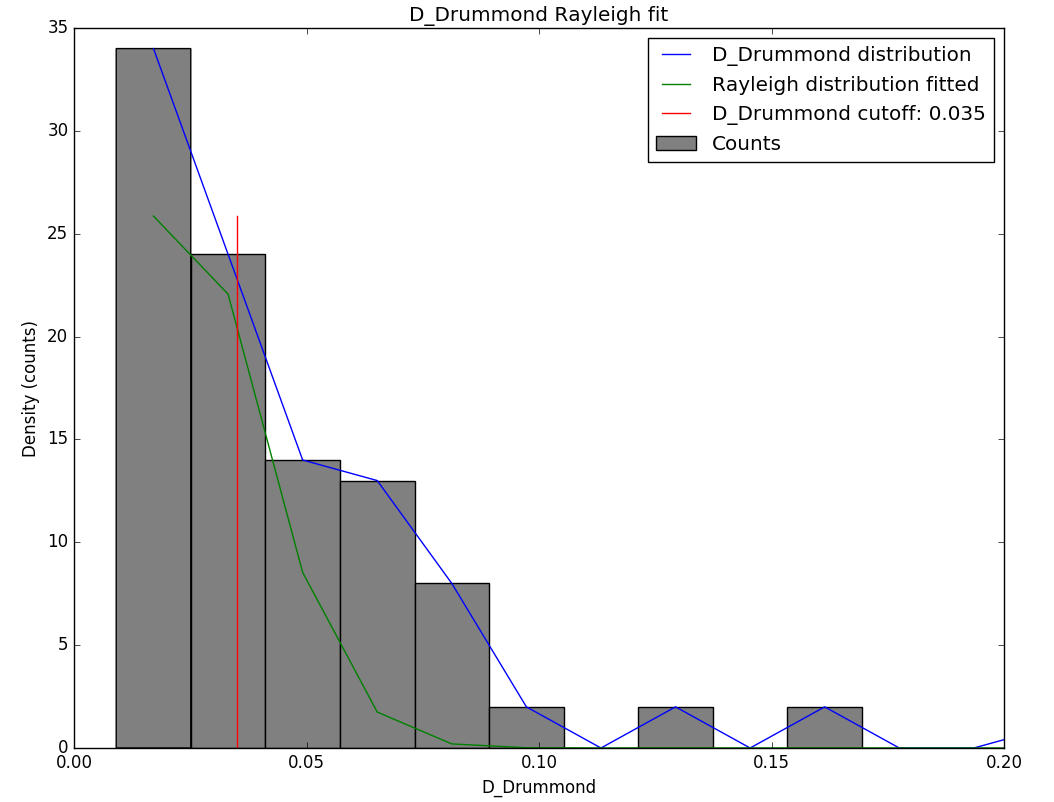

Figure 9 – Rayleigh distribution fit and Drummond DD criterion cutoff.

3 Shower classification based on orbits

Meteor shower identification strongly depends upon the methodology used to select candidate shower members. The sporadic background is almost everywhere present and risks contamination of selections of shower candidates. In order to double check GMN meteor shower detections, another method based on orbit similarity criteria is used. This approach serves to make sure that no spurious radiant concentrations are mistaken as meteor showers.

A reference orbit is required to start an iterative procedure to approach a mean orbit, which is the most representative orbit for the meteor shower as a whole, removing outliers and sporadic orbits (Roggemans et al., 2019). Three different discrimination criteria are combined in order to have only those orbits which fit the different criteria thresholds. The D-criteria that we use are these of Southworth and Hawkins (1963), Drummond (1981) and Jopek (1993) combined. Instead of using a cutoff value for the thresholds of the D-criteria, these values are considered in different classes with different thresholds of similarity. Depending on the dispersion and the type of orbits, the most appropriate threshold of similarity is selected to locate the best fitting mean orbit as the result of an iterative procedure.

The Rayleigh distribution fit indicates that a very small cut-off value is required with DD < 0.035 (Figure 9). The use of D-criteria requires caution as the threshold values differ for different types of orbits. Because of the very small cutoff for the threshold values of the D-criteria, only three classes were plotted:

- Medium: DSH < 0.1 & DD < 0.04 & DJ < 0.1;

- High: DSH < 0.075 & DD < 0.03 & DJ < 0.075.

- Very high: DSH < 0.05 & DD < 0.02 & DJ < 0.05.

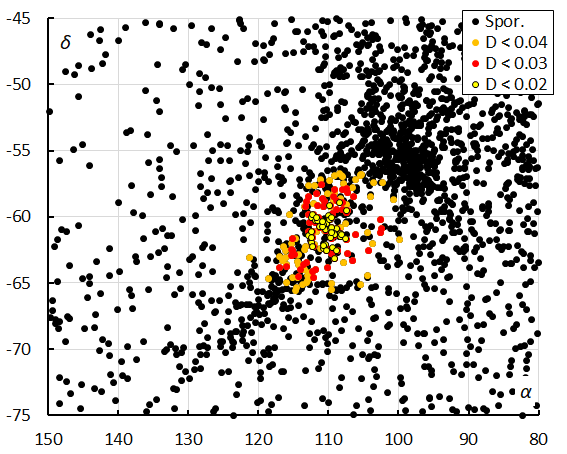

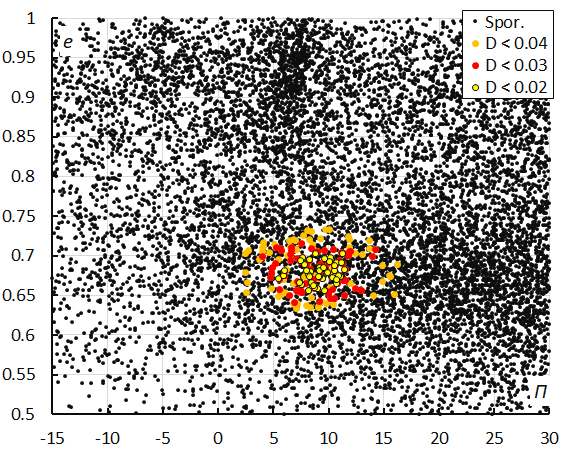

This method resulted in a mean orbit with 98 related orbits that fit within the similarity threshold with DSH < 0.075, DD < 0.03 and DJ < 0.075 between October 10 and 17 in the period 2023 to 2025. The plot of the radiant positions in equatorial coordinates, color-coded for different D-criteria thresholds, has its radiant at 110.4° in Right Ascension and –60.9° in declination (Figure 10). A slightly more tolerant threshold of the D-criteria with DSH < 0.10, DD < 0.04 and DJ < 0.1 results in 173 orbits that fit these threshold values, but with a risk of including contamination with sporadics. Both solutions are mentioned in Table 1.

Figure 10 – The radiant distribution during the solar-longitude interval 196° – 207° in equatorial coordinates, color-coded for different threshold values of the DD orbit similarity criterion.

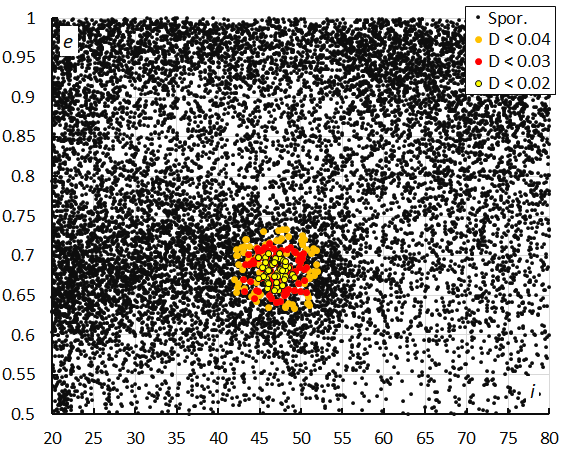

The dense concentration top right from the OEC radiant are the A Carinids (CRN#842), an episodic shower that displayed an outburst in 2025. Most likely both meteoroid streams are components with a common origin. Looking at the Sun-centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates, the radiant appears stretched in Sun centered longitude because of its position close to the ecliptic South Pole. The dense concentration just right from the OEC radiant is again the CRN radiant. A case study about the A Carinids has been published in another report (Roggemans et al., 2026).

Figure 11 – The radiant distribution during the solar-longitude interval 196° – 207° in Sun-centered geocentric ecliptic coordinates, color-coded for different threshold values of the DD orbit similarity criterion.

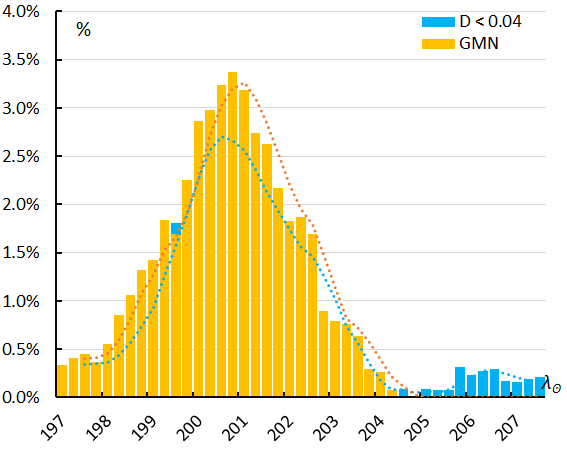

Figure 12 – The percentage of OEC meteors relative to the total number of meteors recorded by cameras at the Southern Hemisphere. Orange is the result for the GMN shower classification, blue for the orbit D-criteria method.

If we look at the ratio OEC-meteors to non-OEC-meteors recorded by GMN at the Southern Hemisphere (Figure 12) in 1.0°-time bins in solar longitude in steps of 0.25°, the best rates occurred around λʘ = 201.0°. The orbit-based shower identification found some orbits after λʘ = 204.0° but the main activity period is situated between solar longitude 197° and 204°. The bias caused by the fact that most GMN cameras at the Southern Hemisphere are installed in Australia and New Zealand, and with less coverage of other longitudes has been solved by combining data collected during three years (2023, 2024 and 2025) to cover the entire time span in solar longitude.

The results obtained from both shower association methods are in good agreement, although both methods had only 95 meteors in common. 106 OEC-meteors were identified by the radiant method but not selected by the orbit method with DSH < 0.075 & DD < 0.03 & DJ < 0.075. Only three orbits were identified as OEC-orbits but not identified by the radiant based method.

4 Orbit and parent body

Looking at the diagram of inclination versus longitude of perihelion, we can see a dense concentration (Figure 13). The concentration right next to the OEC-points are the A Carinids and the concentration near the upper-left are the October 6-Draconids (OSD#745), which were active 10 days later than listed in the MDC working list of meteor showers.

Figure 13 – The diagram of the inclination i against the longitude of perihelion Π color-coded for different classes of D criterion threshold, for λʘ between 196° and 207°.

Figure 14 – The diagram of the eccentricity e against the longitude of perihelion Π color-coded for different classes of D criterion threshold, for λʘ between 196° and 207°.

The diagram in Figure 14 shows the concentration in longitude of perihelion and eccentricity. The concentration at right from the OEC-meteors are the A Carinids, the concentration above the OEC-meteors represents mainly the October Ursae Majorids (OCU#333) and some 31-Lyncids (TLY#613).

Figure 15 shows the concentration in eccentricity and inclination. The cloud around the OEC-meteors are meteors identified by the radiant method as OEC, CRN and some weaker activity sources. The small concentration in the bottom left corner is caused by 62-Andromedids (San#924).

Figure 15 – The diagram of the eccentricity e against the inclination i color-coded for different classes of D criterion threshold, for λʘ between 196° and 207°.

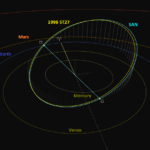

Figure 16 – Comparing the mean orbits for the solutions for the October epsilon-Carinids based on the shower identification according to two methods, blue is for the GMN-method, green for the orbit method with DD < 0.04 and maroon for DD < 0.03 in Table 1, close-up at the inner Solar System. (Plotted with the Orbit visualization app provided by Pető Zsolt).

Table 1 – Comparing solutions derived by two different methods, GMN-method based on radiant positions and orbit association for DD < 0.04 and DD < 0.03.

| GMN | DD < 0.04 | DD < 0.03 | |

| λʘ (°) | 201.0 | 200.7 | 201.1 |

| λʘb (°) | 197.0 | 196.5 | 197.3 |

| λʘe (°) | 204.0 | 207.2 | 204.3 |

| αg (°) | 110.7 | 110.6 | 110.4 |

| δg (°) | –60.4 | –61.1 | –60.9 |

| Δαg (°) | +0.30 | +0.68 | +0.94 |

| Δδg (°) | –0.25 | –0.69 | –0.48 |

| vg (km/s) | 28.9 | 28.6 | 28.6 |

| Hb (km) | 91.1 | 90.4 | 89.9 |

| He (km) | 82.3 | 81.2 | 81.3 |

| Hp (km) | 87.0 | 86.0 | 86.0 |

| MagAp | +0.3 | +0.2 | +0.3 |

| λg (°) | 156.12 | 156.8 | 156.7 |

| λg – λʘ (°) | 315.12 | 315.6 | 315.4 |

| βg (°) | –78.87 | –79.1 | –79.1 |

| a (A.U.) | 3.055 | 3.11 | 3.09 |

| q (A.U.) | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.987 |

| e | 0.677 | 0.683 | 0.681 |

| i (°) | 47.5 | 46.9 | 47.0 |

| ω (°) | 347.6 | 347.8 | 347.8 |

| Ω (°) | 20.6 | 20.8 | 21.1 |

| Π (°) | 8.2 | 8.6 | 8.9 |

| Tj | 2.47 | 2.45 | 2.45 |

| N | 201 | 173 | 99 |

Table 2 – Top ten matches of a search for possible parent bodies with DD < 0.15

| Name | DD |

| 2010 HY22 | 0.046 |

| 2020 VM1 | 0.081 |

| 2010 LG64 | 0.092 |

| 2018 VG1 | 0.105 |

| 2019 WF1 | 0.114 |

| 2019 UQ7 | 0.119 |

| 2016 XP23 | 0.122 |

| 2017 UZ42 | 0.131 |

| (523820) 2011 GN44 | 0.139 |

| 2017 XC | 0.147 |

The Tisserand’s parameter relative to Jupiter, Tj (= 2.47) identifies the orbit as of a Jupiter Family Comet type orbit. Figure 16 shows that the plotted orbits are almost identical for all three solutions. The OEC meteoroid stream intersects the Earth orbit at its ascending node, hitting the planet from deep south of the ecliptic. The position of the descending node in the ecliptic plane is relatively close to the orbit of Jupiter.

A parent-body search top 10 resulted in candidates with a threshold for the Drummond DD criterion value lower than 0.15 (Table 2). Asteroid 2010 HY22 with DD < 0.046 looks a plausible candidate but orbit integrations are required to assess if there is a relationship. The A Carinids, which occur at the same time, also appear to derive from this parent body (Roggemans et al., 2026)

5 Past years’ activity

The only video meteor observations known for this shower are CAMS observations from 2019–2021 published by Jenniskens (2023). A search through historic visual meteor observations confirms that this shower has been observed in the past as a single source that included the A Carinids (CRN#842). The two radiants couldn’t be distinguished by visual observers in the past. A more detailed summary of visual observations has been given in a separate case study on the A Carinids which produced an outburst in 2025 (Roggemans et al., 2026).

6 Conclusion

Global Meteor Network observations confirm the existence of the minor meteor shower known as the October epsilon-Carinids (OEC#1172). The orbit parameters obtained by GMN are in good agreement with those derived by Jenniskens (2023) based on CAMS low-light video cameras, except for the eccentricity and the Sun-centered ecliptic longitude.

Acknowledgments

This report is based on the data of the Global Meteor Network (Vida et al., 2020a; 2020b; 2021) which is released under the CC BY 4.0 license. We thank all 825 participants in the Global Meteor Network project for their contribution and perseverance. A list with the names of the volunteers who contribute to GMN has been published in the 2024 annual report (Roggemans et al., 2025). The following 212 cameras recorded October epsilon-Carinids that have been used in this study:

AU0002, AU0003, AU000A, AU000B, AU000C, AU000D, AU000E, AU000F, AU000G, AU000Q, AU000R, AU000S, AU000T, AU000U, AU000V, AU000W, AU000X, AU000Y, AU000Z, AU001A, AU001B, AU001C, AU001D, AU001E, AU001F, AU001L, AU001P, AU001Q, AU001R, AU001S, AU001U, AU001V, AU001W, AU001X, AU001Z, AU0028, AU0029, AU002A, AU002B, AU002C, AU002D, AU002F, AU0030, AU003E, AU003G, AU003J, AU0041, AU0042, AU0046, AU0047, AU0048, AU004J, AU004K, AU004L, AU004Q, BR000M, BR000Y, BR001M, BR002C, MY0001, MY0002, NZ0001, NZ0002, NZ0003, NZ0007, NZ0008, NZ0009, NZ000A, NZ000B, NZ000C, NZ000D, NZ000F, NZ000G, NZ000H, NZ000J, NZ000K, NZ000L, NZ000M, NZ000N, NZ000P, NZ000Q, NZ000R, NZ000S, NZ000T, NZ000U, NZ000V, NZ000W, NZ000X, NZ000Z, NZ0010, NZ0011, NZ0012, NZ0014, NZ0015, NZ0016, NZ0018, NZ0019, NZ001A, NZ001C, NZ001E, NZ001G, NZ001N, NZ001P, NZ001R, NZ001S, NZ001V, NZ001X, NZ001Y, NZ001Z, NZ0020, NZ0021, NZ0022, NZ0023, NZ0024, NZ0025, NZ0026, NZ0027, NZ0028, NZ0029, NZ002B, NZ002C, NZ002E, NZ002F, NZ002G, NZ002H, NZ002K, NZ002L, NZ002N, NZ002P, NZ002Q, NZ002R, NZ002S, NZ002T, NZ002U, NZ002V, NZ002W, NZ002X, NZ002Y, NZ002Z, NZ0030, NZ0033, NZ0034, NZ0035, NZ0036, NZ0037, NZ0038, NZ0039, NZ003A, NZ003B, NZ003C, NZ003E, NZ003G, NZ003H, NZ003K, NZ003N, NZ003Q, NZ003R, NZ003S, NZ003T, NZ003U, NZ003V, NZ003W, NZ003Y, NZ003Z, NZ0040, NZ0041, NZ0042, NZ0044, NZ0045, NZ0046, NZ0049, NZ004A, NZ004B, NZ004C, NZ004D, NZ004E, NZ004H, NZ004J, NZ004L, NZ004M, NZ004N, NZ004R, NZ004S, NZ004T, NZ004U, NZ004V, NZ004X, NZ004Y, NZ0051, NZ0059, NZ005A, NZ005B, NZ005C, NZ005D, NZ005E, NZ005G, NZ005K, NZ005M, NZ005N, NZ005Z, NZ0061, NZ0063, NZ0065, NZ0066, NZ0067, NZ0068, NZ0069, ZA0002, ZA0006, ZA0007, ZA0008, ZA000C.

References

Drummond J. D. (1981). “A test of comet and meteor shower associations”. Icarus, 45, 545–553.

Jenniskens P. (2023). Atlas of Earth’s meteor showers. Elsevier, Cambridge, United states. ISBN 978-0-443-23577-1. Page 791.

Jopek T. J. (1993). “Remarks on the meteor orbital similarity D-criterion”. Icarus, 106, 603–607.

Jopek T. J., Rudawska R. and Pretka-Ziomek H. (2006). “Calculation of the mean orbit of a meteoroid stream”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 371, 1367–1372.

Moorhead A. V., Clements T. D., Vida D. (2020). “Realistic gravitational focusing of meteoroid streams”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 494, 2982–2994.

Roggemans P., Johannink C. and Campbell-Burns P. (2019a). “October Ursae Majorids (OCU#333)”. eMetN Meteor Journal, 4, 55–64.

Roggemans P., Campbell-Burns P., Kalina M., McIntyre M., Scott J. M., Šegon D., Vida D. (2025). “Global Meteor Network report 2024”. eMetN Meteor Journal, 10, 67–101.

Roggemans P., Vida D., Šegon D., Scott J., Wood J. (2026). “A Carinids (CRN#842) outburst in 2025”. eMetN Meteor Journal, 11, to be published.

Southworth R. B. and Hawkins G. S. (1963). “Statistics of meteor streams”. Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics, 7, 261–285.

Vida D., Gural P., Brown P., Campbell-Brown M., Wiegert P. (2020a). “Estimating trajectories of meteors: an observational Monte Carlo approach – I. Theory”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 491, 2688–2705.

Vida D., Gural P., Brown P., Campbell-Brown M., Wiegert P. (2020b). “Estimating trajectories of meteors: an observational Monte Carlo approach – II. Results”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 491, 3996–4011.

Vida D., Šegon D., Gural P. S., Brown P. G., McIntyre M. J. M., Dijkema T. J., Pavletić L., Kukić P., Mazur M. J., Eschman P., Roggemans P., Merlak A., Zubrović D. (2021). “The Global Meteor Network – Methodology and first results”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 506, 5046–5074.